Occupy Goes Global!

Lützerath

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Lützerath.

Scroll for more

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Lützerath.

Scroll for more

Powerlessness and Empowerment in the Struggle for Lützerath.

By Achim Klüppelberg

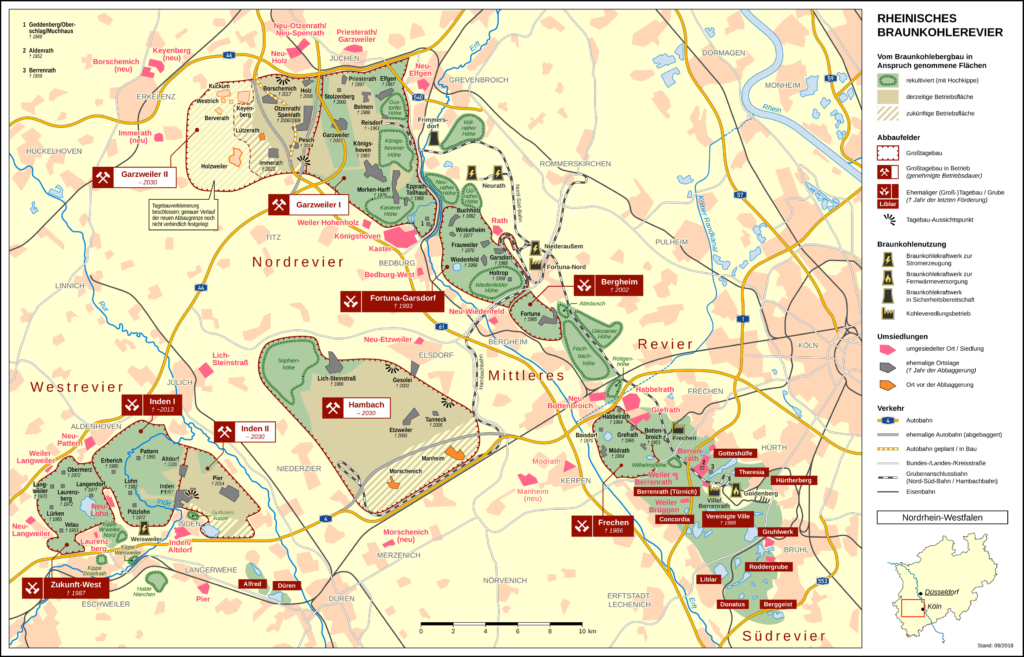

On 14 January 2023, the international climate movement met at the lignite open pit coal mine Garzweiler II in Western Germany to protest the continuous mining business of the corporation Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk, better known as RWE. The culmination of protests took place at the village of Lützerath, which was occupied for about two years to prevent RWE’s large digging machine from destroying its houses to get the coal underground. On that day, between 30 and 39,000 people travelled to the pit known as “Mordor” – an huge moon-like desert, with coal power plants blowing their climate-destroying fumes into the air, clearly visible at the horizon.

1: Rheinisches Braunkohlerevier made by Thomas Römer with Open Street Map data. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The protesters came as individuals or grouped together in different political organisations. Among those were official parties, such as for example the Green Party, large environmental non-governmental organisations, such as Greenpeace, BUND, NAJU, NABU, campact, Fridays for Future, Students, Parents and Scientists for Future, civil society alliances such as Wald statt Asphalt, Alle Dörfer bleiben!, Lützerath lebt!, Klimaallianz Deutschlandand ADAC, queer and LGBT groups, the Christian group Die Kirche(n) im Dorf lassen, hippies, as well as left-wing initiatives from anarchists to occupiers (Kim (first name) 2023; Marlon (pseudonym) 2023; Micah (pseudonym) 2023; Maxi (pseudonym) 2023; Fabian Pieper (full name) 2023).[1] International guests also came to the event. Prominently, Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg gave a speech. All of these groups came together around the goal of defending Lützerath against RWE to keep the coal in the ground, protect local villages, and to ensure that Germany would stay committed to her 1.5 °C-climate goal as agreed upon in the Paris climate agreement. If all the coal beneath Lützerath would have been used in thermal power plants, Germany would have failed her climate commitments. Crucial in this regard were climate tipping points, which if overstepped would spiral the situation out of control (Micah 2023). For activists, the village represented the physical 1.5°C-limit: if it were to fall, so would the climate goals (Maxi 2023). Apart from this tangible aim, left-wing groups also wanted to create an alternative society in Lützerath, as had been practised in other squats for example at the protests at the Hambach Forest (“Hambi”), the Dannenröder Forest (“Danni”), and others (Marlon 2023; Maxi 2023).

If this effort would have been successful, the beneficiaries could have been found on the local, regional, federal, and European level. For the locals, the survival of their homes and their used way-of-life was at stake. For the region, the proposed stop of lignite mining at Garzweiler could have had direct positive impact on groundwater levels, pollution, loss of ecosystems, biodiversity, and agriculture. For Germany, the future of the so-called Energiewende was on the line. In Europe, Garzweiler was and is one of the largest lignite mines and thus one of the biggest sources of CO2-emissions in the energy sector. By stopping its exploitation, the overall greenhouse gas emission balance of the continent could have been reduced.

Feeling the need to become active and protest the injustice of climate destruction, I travelled to Lützerath and participated in the protests on 14 January 2023. In the weeks after, I was able to get in contact with five other participants. We conducted interviews during the spring of 2023. The information presented in this text stems from both these interviews and my own experiences on-site, as well as literature on the events. Four of the interviewees were female and one male. While being between 27 and 34 years old, they came from the regional cities of Krefeld (about 60km north of Lützerath), Darmstadt (about 140km to the Southeast), Gießen (about 150km to the Northeast) and the area around Frankfurt. All spoke German with me and had a university background. Their fields of expertise were chemistry, hydrology, biodiversity, agriculture, biology, and pedagogy. Two were not politically organised, while two others were engaged in non-governmental and left-wing political groups. One person – Fabian Pieper – was a Green Party member and elected representative in Krefeld, active in the environmental executive committee of the city.

Past – Situating the village in the rural landscape.

Lützerath was a tiny village. It went back a long way, as it was first mentioned as Lutzelenrode in 1168. The Wachtmeisterhof was run by a Cistercian monastery based in Duisburg from 1265 until 1802, to facilitate agriculture. Before eviction, eight people officially lived there in June 2022. But it used to be more as by then most people had already taken the compensation offer from RWE and moved away. Nevertheless, Lützerath became a focal point of the climate justice movement and dozens to hundreds of people squatted the old farmhouses to stop the coal mine eating away the ground the hamlet was standing on. They built new dwellings, tree houses, water pipes, tents, and other facilities for continuous settlement (Marlon 2023). All of those were technically not authorised by any provincial administrative body. But they were also not illegal, as most of these structures were built on ground that belonged to sympathetic villagers who invited activists to come and live with them. The most prominent of these villagers was Eckart Heukamp, who lived in the old Wachtmeisterhof. He was the last official resident of Lützerath (de Gregorio 2020). Therefore, up until the end in late January 2023, the place was inhabited by more people, stemming from all kinds of regions and engaged in many different activities.

2: Occupied Backsteinhof in Lützerath 2021. “1,5°C means that Lützerath stays!”; “Excavator for sale for 1,5°C”. By © Superbass CC-BY-SA-4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

The strategy of the climate movement regarding Lützerath was plentiful. First, an enormous effort was made to inform people about what was going on. The aim was to mobilise as many as possible for both the actual squats in Lützerath but also for the large demonstration on 14 January 2023, which became known as Tag X (“Day X”), a synonym for the day before Lützerath was supposed to be dug away and evictions were about to start. This demonstration was a cornerstone of the strategy, but by far not the only one. Numerous demonstrations throughout Germany were conducted in solidarity, information events held, posters and stickers distributed, social media campaigning included, and left-wing activists tried to revive Lützerath. They started living there and to build and grow a space in which utopia could be realised, despite or maybe even because the lignite mine got larger and larger, encroaching upon the hamlet.

Squatting Lützerath to prevent RWE from digging out the coal had the aim to postpone the day when the company could finally make profits from the resource by indefinitely dragging out the process and increasing costs. This tactic was successful in the struggle for the Hambach Forest since 2012 (Hambi bleibt!). The successful struggle in Hambach also motivated my interviewees Kim, Marlon, and Maxi to join the protests for the survival of Lützerath (Kim 2023; Marlon 2023; Maxi 2023).

Furthermore, the official story justifying the usage of coal beneath Lützerath based this climate-harmful endeavour on the procurement of arguably essentially needed energy supply for the whole country, which allegedly could have overruled climate commitments. On the one hand this was a path-dependent continuation of German energy policy from the times of industrialisation in the 19th century until today (RWE).[2] On the other, it was a stern 180° change of position for the new government around chancellor Olaf Scholz, who led a coalition between Social Democrats, the Green Party and the Liberals that presented itself as being committed to mitigating climate change during election campaigns in 2021 (cf. with Swyngedouw 2013, 10).

Ostensibly, the coalition changed its announced policy back to conventional German energy strategies because of the war between Russia and Ukraine that dramatically escalated on 24 February 2022, the following deliberate and unilateral decision by the government to stop fossil fuel imports from the aggressor, the destruction of Nord Stream I and II, as well as the intentional inability to create a sustainable change in Germany’s energy mix based on renewables now and during the last decades.[3] To add injury to insult, the Green Party both ruled the federal energy ministry and the regional environmental ministry concerned with Lützerath: Instead of fighting RWE, they embraced the company’s goals and sanctioned the destruction of the village.[4]

Contradicting this change in policy, the highest court of the country had previously decided several lawsuits in a way that practically elevated climate change mitigation policies into constitutional law (Pieper 2023; BUND 2021). The German government argued on the basis of limited scientific evidence heavily influenced by RWE and issued by the regional economy ministry that the coal beneath Lützerath would have been needed to avoid the breaking down of energy systems during the winter period of 2022-2023 (Micah 2023; Reichert 2023). To formulate a compromise, the Green Party turned in favour of digging out the coal under Lützerath and forfeiting the 1,5°C-goal, but in exchange wanted to make RWE stop at the Garzweiler lignite pit after that, protecting the villages Kuckum, Berverath, Keyenberg, Oberwestrich and Unterwestrich that lay west of Lützerath and that the company wanted to destroy next. On 04 October 2022, RWE, regional economy minister Mona Neubaur and federal economy minister Robert Habeck (both from the Green Party) publicly proclaimed this deal at a press conference. Furthermore, the federal stop of generating electricity by burning lignite was to be antedated from 2038 to 2030, which the Green Party marketed as a success (Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland 2023). In opposition to that alternative scientific reports were made, questioning the soundness of this assessment and this deal (Micah 2023). Several already existed before the decision was taken (Scientists for Future 2023). Ignoring science, RWE wanted to be fast and to go ahead before a renewed discussion of the matter could possibly change the decision.

The activists hoped that by dragging out the protests, the regional and the federal governments could have time and feel the urge to reassess, which could have given the Green Party some leverage to prevent the destruction of Lützerath (Pieper 2023, Micah 2023, Kim 2023). Especially the latter were strong motivations for Fabian Pieper, Micah and Kim to join the demonstration on 14 January 2023.

3: “Let’s go to Lützerath! Stop eviction! For Climate Justice!” – Mobilising poster of the climate protests taking place at the Garzweiler lignite mine. Provided via Fridays for Future for distribution. Co-production of the different initiatives stated at the bottom of the poster. The yellow X represents “Tag X”, which became a symbol of anti-coal protests in Germany.

According to RWE, the lignite mine Garzweiler produced up to 30 million tons of coal on an area of 35 km² by digging away 100-120 million m³ per year (RWE). During the last years, the mine was continuously expanding, eating away fertile agricultural land and rural communities on its way to Lützerath. With the climate crisis dramatically escalating during the last five years, the village became a focal point for the German and international climate movement.

4: Lützerath in Western Germany, close to the Netherlands and west of Cologne. Map made with Google Earth, DATA SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO. Image Landsat/ Copernicus.

5: Lützerath and the open-pit Lignite mine Garzweiler (including the now gone village of Garzweiler) in 2003. Map made with Google Earth, image © 2023 GeoContent, image © 2023 AeroWest.

6: Lützerath and the encroaching pit (Garzweiler is gone now) in 2021. Map made with Google Earth, Image © 2023 CNES/ Airbus.

7: Zoom-in on Lützerath in 2021. Map made with Google Earth.

8: RWE’s large digging machine standing opposite of the town of Lützerath at the top-right corner, surrounded by police. The yellow-vested-people standing next to the excavator are private security guards defending the machine against squatting attempts by protesters. By the author, taken on 14 January 2023.

Events flamed up on 11 January 2023, when the police started the forceful eviction of activists from Lützerath and the surrounding area (Rheinische Post 2023, Hill 2023). While preparing for day X, activists had erected barricades out of stones, bricks, logs, concrete, and steel. They also tried to block paths and roads with the basic tools they had available. Fences that were built by the police were torn down by activists. Again and again, protestors tried to occupy eviction equipment and RWE’s digging machinery. At the same time, many demonstrations popped up around the whole republic, including protests in front and inside of the Green Party’s regional headquarters in Düsseldorf (Focus Online 2023). Activists both held out on the roofs of buildings and in tree houses, where it was very hard to evict them, and in a tunnel, two guys dug out beneath Lützerath (Micah 2023, Schönberg 2023). At the same time, protests targeted the central business building of RWE in Essen, where people chained themselves to the plant’s gates. At the fellow lignite mine in Hambach, activists squatted one of RWE’s large excavators in solidarity.

Besides the struggle to protect the climate, it was also important to show that the German state would dispossess some of its rural citizens for outdated resource extraction, even in 2023 (Marlon 2023). People had to lose their homes to fuel RWE’s profit interests. Furthermore, in many of these small villages that already were or were to be destroyed, churches were being desecrated even though the local people wanted to continue their operation (Die Kirche(n) im Dorf lassen). In this regard parts of the struggle also had a religious component to it.

The large, rainy and muddy demonstration on 14 January 2023 was the culmination point of all those activities. It was a powerful protest, certainly one of the larger climate demonstrations in Germany. Nevertheless, the amount of people attending was a contested issue for the interviewees. In the immediate aftermath of the demonstration, it became apparent that there was a large discrepancy between the number reported by the police (15,000) and the one by activists (50,000) (Pieper 2023). The actual number might have been between 30,000 and 39,000 (Maxi 2023, Düperthal 2023, Pieper 2023). This discrepancy was one of many contested issues in regard to media reporting on the demonstration that undermined enthusiasm in the political process and the independence of the media (Pieper 2023, Maxi 2023, Micah 2023). The interviewees evaluated the turnout of the demonstration differently. Maxi was disappointed. Following the mobilisation success of several Fridays for Future demonstrations in Germany and the fact that 80,000 people would go and see a football game, she hoped for 200,000 people showing up at Lützerath (Fridays for Future Germany 2021; Maxi 2023).[5] On the other hand, for Marlon and Kim the actual turnout was a success giving hope for the movement and for future protests (Marlon 2023; Kim 2023).

However, the demonstration and all the different creative actions in so many places aiming at preserving Lützerath and keeping the coal in the ground, were futile in the end – Lützerath was destroyed and the coal has been dug up, public climate commitments, the Paris climate agreement, and continuing protests notwithstanding.

Present – The village is gone, but Lützerath lives on.

Unfortunately, the protests that went on for years and culminated in the big demonstration on 14 January 2023 were unsuccessful in the sense that Lützerath did not survive. Protesters, activists, and climate enthusiasts had to realise that in this instance, the combined force of big capital in the form of RWE, a compromising regional and federal government, as well as a chancellor who took climate commitments by himself and by his own party not serious, the limits of their influence was reached. Marlon described in detail the experience of reaching physical limits on 14 January 2023. While trying to breach police barricades to get into Lützerath, she and others were forcefully stopped (Marlon 2023). At other places, people were hurt on both sides and the physical limits of being unable to reach the village became apparent.

Institutionally, the regional and federal governments had simply decided that this would happen now, ignoring the years of protests and the emergence of alternative scientific reports questioning the necessity of the whole endeavour. With their behaviour they showed clearly, where the institutional limits of the protesters were.

Limits also became tangible in a social dimension after the demonstration. The population was split in three camps: supporters of Lützerath and the protests, supporters of RWE and the police, and the broad mass that did not want to take notice of the dramatic events taking place at Garzweiler in the context of the climate crisis. Fabian Pieper described how he had mostly heard negative reports from the protests before 14 January 2023 and how afterwards the internal discussion within the Green Party was very polarised. In discussion with his local party colleagues, he wrote an official protest letter to the regional government, in which the Green Party held significant power. Unfortunately, the response was not in favour of these complaints, and the letter was ignored (Pieper 2023). To add injury to insult, he reported that the press representative of the Green Party was beaten up by the police during the demonstration while trying to reach Lützerath, adding in hindsight to a felt sense of disappointment at the rank and file of the party (Pieper 2023). Adding to this, the head of the police on-site was also a Green Party member, showing in a sense contradicting party action (Pieper 2023). Here the social limits of the protests became tangible.

After the protests, the interviewees still felt linked to the events and what had happened on-site, but they had different opinions about it. Marlon felt sad, angry and bewildered that Lützerath was evicted, although she had prepared herself for this possible outcome. She was very shocked, how fast in the end authorities evicted people from the village. Nevertheless, the large demonstration gave her hope for the future of the struggle. She said “The fight will become even more important, because Lützerath is lost” (Marlon 2023).[6] Maxi showed a more stoic assessment, as for her nothing has changed now that Lützerath is gone. If RWE was to dig up the next town, Keyenberg, she would once again be there to protest, convinced that then even more people would show up, especially the youth whose future was being robbed (Maxi 2023). Kim agrees, as she also has not lost hope for the cause as a whole, due to the fact that so many people engaged with Lützerath. These would continue the struggle and she believes that then institutional politics would have to listen (Kim 2023). Fabian Pieper disagrees, as Lützerath was a failure. Not only for him personally, but also for his party. Decisions were taken in a very non-transparent way as quickly as possible to prevent environmental organisations to react. This would have caused a tremendous loss of faith in the Green Party in particular and the government in total. For him, all of this feels bad (Pieper 2023). Micah was disappointed, too (Micah 2023). Unrelated to their testimonies, the fact that the police used transporters from the actual private company RWE for carrying the evicted activists away, showed how close the connection between capital and executive had become (Düperthal 2023). This underscores doubts opposing the soundness of the political system.

Therefore, the biggest limit, or better loss, was that the protests as a whole were not successful in this instance. Where once the village became home for many “old” citizens and climate activists, it now ultimately fell victim to the company’s excavator. Few things in the landscape still tell of its former existence, the so hard-gained spaces for creativity, freedom, and housing are gone. On the first look, this was a bitter disappointment for many (Maxi 2023).

With the demonstration back in the past and so many activities gone by, one should ask oneself what could have been done better by us climate activists to ensure that this campaign could have been successful. Marlon realistically stated that a success, such as at the Hambach Forest, was the exception not the rule (Marlon 2023). Nevertheless, the struggle for Hambach can give inspiration of what strategy had worked and which had not. One thing that became topic during many interviews was the noticeable division between protesters (Micah 2023, Kim 2023, Pieper 2023, Marlon 2023).

Basically, the dividing line went across the question of how far one should go to protect Lützerath. Most protesters went to the demonstration but had no intention to confront the police, to deliberately disregard their orders, or to squat Lützerath. This position was only taken by a minority of dedicated activists, who from their own understanding also wanted more than protecting the village: they were out to protect a space where utopia could become reality (Marlon 2023, cf. with Swyngedouw 2013, 13). Overwhelmingly left-wing and with a large portion of anarchists amongst their ranks, this group had goals that were not shared by many of the other protesters (Kim 2023, Micah 2023, Pieper 2023). They were willing to go into the confrontation with the police, risking their health and proceeding lawsuits in the aftermath (Maxi 2023).

For Kim, this did not feel well during the demonstration (Kim 2023). She reports that some anarchists went around the demonstration to get people to join heading towards the village and the police chains defending it (cf. with Pieper 2023). She also noticed that multiple people around her did not want to go. Apart from that, there were also speeches given at the rally point, like for example by Greta Thunberg. After she spoke, there was also another speech given that used very strong language that indicated that people should now turn towards Lützerath (Pieper 2023). Many did not follow, as apparently this was not a consensus amongst protesters. This divide was negatively felt by some and certainly did not strengthen the movement (Micah 2023, Pieper 2023, Kim 2023). The sour discussion in mainstream media of the protest did not help in this regard. Maxi had a more nuanced point of view. She did not notice any conflicts of this sort during 14 January 2023, but was aware of these dividing conflicts beforehand.

At the bottom of this division lies an ethical question: is it allowed to use force unsanctioned by authorities to protect the environmental basis for tomorrow (Malm 2021, 7-9)? While certainly not a young question, the climate movement and especially Fridays for Future were in the last years very successful in mobilising people for large protests on the basis of explicitly peaceful demonstrations. Initiatives such as Last Generation or Extinction Rebellion added the old anarchist principle of peaceful direct action to the mix. But in the case of the Hambach Forest, this was not enough. Only the concerted effort of left-wing protesters that squatted the forest and lived in tree houses, erected barricades and always came back once they were evicted, together in unison with all other forms of protest saved the forest. If we were to learn from Hambach, then this is the lesson: there needs to be unison amongst the protesters and both camps need to come together for the common goal. If not – and this shows Lützerath – mainstream media will polarise conflicts and divide the protests into good and bad ones, leading to a weakening of both and a silencing of the main message.

Parts of the speeches at the rally point focussed on intersectionalism, linking the struggle at Lützerath with anti-racist fights in the USA, sexism in Germany, anti-colonial indigenous struggles in South America and xenophobia in Europe (cf. with Swyngedouw 2013, 17). For Fabian Pieper, this was not a useful strategy. In his eyes, this was rather perceived as deterring, detrimental to the actual mobilisation effort. The identification of environmental protection and racism led to a logical reasoning like “if you are against protecting the environment, you are a racist” (Pieper 2023, cf. with Whyte 2017, 157-158). This would not be helpful, as it could not motivate ordinary people to join the protests. Here, different theoretical approaches became apparent. Micah later thought about this in a more neutral way, having heard for the first time of these connections at this event (Micah 2023).

Marlon noticed another important point. For her, the strategy of those activists that actually wanted to get into Lützerath was too one-dimensional. It would have been better to use multiple creative forms of protest. The simple attempt to frontally breach police chains was doomed to fail, which was in a sense a disheartening situation for her (Marlon 2023).

In the aftermath of 14 January, another downfall of the movement became obvious. Our communication strategies were inadequate. In many cases it was not possible to get based information for the general public (Pieper 2023, Kim 2023, Micah 2023). This void was filled by mainstream media such as the state’s news show Tagesschau, Springer’s right-wing newspaper Welt,and the news magazine Spiegel. All of these only presented biased information and usually not in favour of the protesters. Micah even spotted a lie in the reporting made by the police, saying that officers would have been there to protect people from falling down into the mining pit, something that definitely was not the case (Micah 2023; image 8). A generally observed strategy was to focus attention on the violence that happened between the police and activists at the side of the protests, while the peaceful demonstration of the dozens of thousands of others were largely silenced. Interviews were framed and cut in a way that it was impossible to actually get a full picture on the situation (Pieper 2023). Sadly, environmental activists failed in filling this void, often even appearing as unreliable sources themselves (Micah 2023, Pieper 2023). For Micah, it was important to present more based scientific information in a very clear manner, to at least give people a chance to form a serious opinion on this issue (Micah 2023). The movement needs unity and a better and more comprehensive, source-based communication strategy.

Many strategies employed were in themselves useful. In general one can say that the squatting of farm houses, the construction of tree houses and tripods, and creative protests including both peaceful protesting and direct action events proofed to be successful in a sense that it increased the costs for RWE and prolonged the time schedule under which the coal extraction activities were planned. It was useful that some people squatted RWE’s excavators and that others had erected barricades against being evicted. It was important to write texts and to inform both other environmental activists and the general public about what was going on. Especially also to counteract the mainstream narrative of the protests. Mobilising via diverse channels, amongst others via the messenger Telegram and through Facebook proved to be effective. Mobilisation strategies in general had shown considerable success as indeed many people across the republic and far away became aware and active in the struggle to protect Lützerath. The fact that Greta Thunberg, Luisa Neubauer, and other international figures of the climate movement came to Lützerath and protested showed considerable success for the mobilising strategy. I personally find it astounding, how the activists created logistics for the struggle on-site, in such a relatively remote area with the few resources that were available. Surely, the demonstration on 14 January 2023 was a key example for that, but also the years-long struggle before that. During the days before and at the demonstration, when the police moved into Lützerath to evict the occupiers, two strategies proved to be exceedingly successful in postponing their operation. First, by moving up to the roofs of the buildings, it became very difficult for the police to arrest the squatters and to destroy those edifices. The second one was the construction of a secret tunnel, within which two activists hid themselves, thus making elaborated groundworks above impossible (Schönberg 2023).

Ultimately, and despite the diverging interests among the group of protesters, it was a large success to mobilise so many people under one umbrella and for one purpose. This is a powerful message that gives hope for future protests (cf. with Marlon 2023). These positive strategies can be replicated at places of further struggles against lignite mining in Germany.

Future – Inspired by Lützerath, working towards an end of German coal

Unfortunately, the village is gone. It will not have a future. The people who have left, who were evicted and the ones that took the deals offered will not return. To cover their tracks and hide the hideous landscape they have created, RWE and the province plan to fill the huge mining pits with billions of litres of water from the Rhine to create several huge lakes (Sieben 2022). The realisation of this idea is highly questionable (cf. with Kim 2023). During the last summers, the region experienced droughts and the Rhine’s water levels had dropped. To continuously divert a significant part of this river will not be a sustainable solution, as everyone downstream will suffer. It will not work.

Nevertheless, Lützerath did a lot to many individual people in particular and the climate movement as well as the general discourse in general. For me, the urgency to act within the context of the ongoing climate crisis is apparent, the greediness of the coal company appalling, the complicity of large parts of the political establishment open for everyone to witness, disregarding previous announcements, climate agreements, and election programmes. People see this and the discrepancy cannot be hidden anymore. The German state does not take its own climate goals serious. Instead it promotes the usage of the dirtiest energy option there is: open-pit lignite mining.

Here Maxi elaborated on a very important issue for activists that needs to take place after the events. People have to talk with each other about their experiences, about what went right and what went wrong, in order to get over the disappointment of failure and to avoid depression. It is therefore necessary to watch out for one another, and to not silently carry these feelings home and to only deal with them alone (Maxi 2023).

On another note, Marlon said that the experience in Lützerath during the blockades gave a lot of hope and ideas on how to live to create a better future. Maybe even for how to build a new society without exploitation. Therefore, Lützerath lives on in the minds of the activists, as it became a household term describing what failed climate policy means in concrete terms. All interviewees agreed that Lützerath means a lot to them, also months after the protests had failed (Maxi 2023, Marlon 2023, Pieper 2023, Micah 2023, Kim 2023). This fundamental experience cannot be undone.

One important question to ask in this regard is whether RWE will have to stop digging coal in the area – as this was the deal with the government – or whether they will be allowed to continue. If they will be stopped, at least Lützerath’s neighbouring villages could be saved and the area preserved (Pieper 2023).

That being written, it is for me more probable that another village at the Garzweiler lignite mine will be threatened to be dug away. If that happens, people will go there again and take the spirit of Lützerath with them to continue the struggle. Then even more people will support it and the next village will be saved, as strategies evolve and divisions amongst the movement dissolve. We have one planet and only one joint future on it. Globally, Lützerath might only be one of many frontlines of the climate crisis. But the more we zoom in, the more important it becomes for the people closeby. Another world is possible, we just need to be brave enough to act outside the established norms. Lützerath has shown that change will not come from above, but that it is already here in the present, created by average people who dared to act. This gives hope to continue, hope to accept this setback, and hope to work together for a better world, in which we do not jeopardise everything for the greed of a few but powerful people. Lützerath lives on.

References

Interviews

Kim (works with water protection and dynamic in Germany). Interview on 25 April 2023 via Zoom in Stockholm. First name basis.

Marlon (Climate activist, Gießen, Germany). Interview on 22 April 2023 via Zoom in Gießen and Stockholm. Pseudonym.

Maxi (Climate activist, near Frankfurt, Germany). Interview on 24 April 2023 via Zoom in Stockholm. Pseudonym.

Micah (Climate activist, Darmstadt, Germany). Interview on 05 April 2023 via Zoom in Darmstadt and Stockholm. Pseudonym.

Pieper, Fabian (communal politician in Krefeld-Fischen, Green Party, Germany). Interview on 12 April 2023 via Zoom in Krefeld and Stockholm.

Literature

Bund für Umwelt- und Naturschutz Deutschland/ Friends of the Earth Germany (2021). “Bahnbrechendes Klima-Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts”. 29 April 2021, https://www.bund.net/service/presse/pressemitteilungen/detail/news/bahnbrechendes-klima-urteil-des-bundesverfassungsgerichts/ [2023-07-05].

de Gregorio, L.: “Der letzte Kämpfer”. Taz, 25 October 2020, https://taz.de/Der-Hausbesuch/!5719920/ [2023-06-23].

Die Kirche(n) im Dorf lassen: “Wer wir sind”. https://www.kirchen-im-dorf-lassen.de/%C3%BCber-uns/ [2023-07-04].

Düperthal, G. (2023). “Die Polizei bediente sich der Transporter von RWE. Grundrechtekomitee dokumentiert Polizeigewalt bei Räumung von Lützerath. Reul bestreitet Verstöße”. junge Welt, 18/19 March 2023.

Focus Online (2023): “Protest Gegen Lützerath-Räumung. Aktivisten besetzen erneut NRW-Parteizentrale der Grünen”. 12 January 2023, https://www.focus.de/panorama/welt/protest-gegen-luetzerath-raeumung-aktivisten-besetzen-erneut-nrw-parteizentrale-der-gruenen_id_182852884.html [2023-06-30].

Fridays for Future Germany (2021): “Fridays for Future: Bundesweit demonstrieren 620.000 vor der Bundestagswahl für mehr Klimaschutz”. 24 September 2021, https://fridaysforfuture.de/fridays-for-future-bundesweit-demonstrieren-620-000-vor-der-bundestagswahl-fuer-mehr-klimaschutz/ [2023-06-30].

Hambi bleibt!: “10 Jahre Besetzung Hambacher Forst”. https://hambacherforst.org/besetzung/ [2023-06-28].

Hill, J. (2023): “Lützerath eviction: German police drag climate protesters from coal village”. BBC News, 11 January 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-64233676 [2023-07-20].

Malm, A. (2021): How to blow up a pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire. Verso.

Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland rnd (2023): “Das Dorf Lützerath. Chronologie eines jahrelangen Streits im Braunkohlerevier”. https://www.rnd.de/politik/luetzerath-chronologie-eines-jahrelangen-streits-im-braunkohlerevier-XLEQDWXTOSNYCO6RFNUVJBDRO4.html [2023-06-29].

Reichert, I. a. Puttfarcken, Lena (2023): “Was du wissen must, um die Debatte um Lützerath zu verstehen”. Quarks, 23 January 2023, https://www.quarks.de/technik/energie/luetzerath-braunkohle-energieversorgung-klimaziele/ [2023-07-12].

Rheinische Post (2023): “Die letzten Tage von Lützerath – eine Chronologie”. 16 January 2023, https://rp-online.de/nrw/staedte/erkelenz/braunkohletagebau/luetzerath-raeumung-die-letzten-tage-des-dorfes-im-braunkohlerevier-eine-chronologie_bid-83087941#0 [2023-06-29].

RWE: “Tagebau Garzweiler”. https://www.rwe.com/der-konzern/laender-und-standorte/tagebau-garzweiler/ [2023-06-29].

Schönberg, K.: “Tunnel in Lützerath. Pinky & Brain halten die Polizei auf”. Taz, 13 January 2023, https://taz.de/Tunnel-in-Luetzerath/!5908646/ [2023-07-04].

Scientists for Future Germany (2023): “Offener Brief. Ein Moratorium für die Räumung von Lützerath”. 11 January 2023, https://de.scientists4future.org/offener-brief-ein-moratorium-fuer-die-raeumung-von-luetzerath [2023-07-12].

Sieben, P.: “Riesiger See in NRW: Milliarden Liter Wasser aus dem Rhein sollen umgeleitet warden”. Merkur, 06 December 2022, https://www.merkur.de/deutschland/nordrhein-westfalen/streit-kritik-tagebau-hambach-rwe-forst-koeln-aachen-zrw-riesiger-see-nrw-hambacher-see-neu-91939133.html [2023-07-04].

Swyngedouw, E. (2013). “Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures”. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 2013 (24:1): 9-18.

Whyte, K.P. (2017). “The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice, and U.S. Colonialism”. REDINK, Spring 2017 (191): 154-169.

[1] BUND: Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland; NAJU: Naturschutzjugend im NABU; NABU: Naturschutzbund Deutschland; ADAC: Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club.

[2] RWE introduces the coal mine on its website by pointing out that lignite would have been dug at Garzweiler for more than 100 years.

[3] The Social Democrats were part of the federal governments from 1998 until 2009, and from 2013 until now. Olaf Scholz himself was part of the cabinet Merkel I as minister for labour and social issues from 2007-2009 and Merkel IV as minister of finance as well as vice-chancellor from 2018-2021. As such, it is to an extend his fault that the term Energiewende has continued to represent an empty phrase without material substance.

[4] This is only the view of the author.

[5] Cf. with testimony of Fabian Pieper, who himself went to Fridays for Future demonstrations in support of Lützerath before 14 January 2023.

[6] Translated by the author from “Weil Lützerath verloren ist, ist der Kampf immer wichtiger.”