Occupy Goes Global!

Seoul

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Seoul

Scroll for more

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Seoul

Scroll for more

The Case of Food Cooperative ‘Hansalim’ in South Korea

Joohee Lee

With the growing concerns over the ongoing global sustainability crises such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, social movement-based momentum for change is needed more than ever. Indeed, top-down, country-level efforts to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs) have exposed a clear level of political limitations and inertia over the years. Non-governmental and local-level SDG action, on the contrary, has seen significant growth thanks to the flexibility and locality embedded in their unconventional ideas and innovations. Cooperatives are one of those innovators on the front lines of SDGs. This entry sheds light on the unique role of food cooperatives, defined as consumer-owned food distribution organizations, in enhancing climate awareness and action among customers by promoting healthy food, fair trade, and grassroots movements.

Background on the Hansalim Movement

As a case study, I investigated a South Korean food cooperative called Hansalim (or 한살림 in Korean), which means ‘saving all living beings’ and also ‘living in unity.’ Hansalim began as a small local rice shop in Seoul, South Korea in 1986, and is now one of the oldest and largest food cooperatives in the country. Its initial goal as a community-serving food network was to connect rural and urban areas for fair exchange of fresh and organic food. This agricultural and food innovation quickly appealed to customers in urban areas, who were interested in healthy eating and mutual growth with rural communities. In 2017, Hansalim supplied $423 million worth of ethically produced and traded food items from 2,000 individual farms to approximately 644,000 families (Hansalim, 2016). As of 2022, the cooperative is running 240 local stores across Korea (See Figure 1). They continue to evolve not only in terms of numbers, but also in terms of creativity that can alter the unjust and unsustainable food-climate-energy system with grassroots power.

In 2014, Hansalim received the One World Award, which honors experiments that exhibit positive and creative examples of globalization based on sustainability, for its accomplishments and inspirations (One World Award, n.d.). Hansalim’s approach to food-energy-climate justice has also been recognized and discussed in academic work (Kim, Lee, Shin & Jang, 2020; Pak and Kim, 2016; Choi, 2009). One study positively evaluated the co-op by showing that Hansalim illustrates a successful and practical example of an intellectual movement based on ecophilosophy and bio-regionalism. (Pak and Kim, 2016; Suh, 2015). The concept of Hasalism was also viewed as a trust-based social economy that brings urban and rural communities together in a globalized market environment (Choi, 2009). In the following sections, I explore the philosophical and organizational drivers behind the Hansalim movement.

Figure 1: A local Hansalim store in Seoul, South Korea. Image by Joohee Lee.

Hansalim’s Organizational Values and Principles

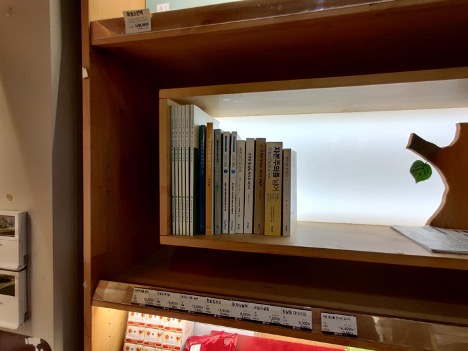

According to Hansalim, their movement is based on five core principles: 1) respect for life, 2) respect for Mother Earth, 3) respect for community, 4) respect for ecosystems, and 5) the spirit of ‘change begins from me’ (Hansalim, n.d.a). These principles have guided the food cooperative’s three focus areas. The first and foremost focus area is to save people’s tables. To fulfill this goal, Hansalim connects producers and consumers directly (75% of total sales revenues go to the contract farmers), organizes educational programs and campaigns to promote food sustainability, and gets involved in policy-making processes to enhance the country’s food production and distribution systems. Secondly, to save our agriculture, Hansalim supports farmers who produce safe and organic food, creates funds to protect ecologically sound local farms, and organizes activities between rural and urban communities. Last but not least, Hansalim is committed to saving our life and planet by promoting the value of our life and planet through research, education, publication activities, and practicing alternative ways of living in harmony with nature and neighbors. Hansalim’s principles of everyday sustainability and well-being show the potential in cooperative-led food-climate-energy justice action as a bottom-up movement for sustainable consumerism and climate activism. As seen in Figure 2, Hansalim local stores serve not only as food stores but also as small, local learning commons for grassroots-based sustainability movements.

Figure 2: Hansalim stores offer and recommend books concerning food sovereignty and environmental justice. Image by Joohee Lee.

Hansalim’s Efforts in Local Climate Action

In the face of the rapidly growing threat of the climate crisis, Hansalim’s passion for agricultural sustainability has naturally extended to the issue of food-climate-energy justice due to the inseparable linkage between the three areas for sustainable living. While their core organizational goal is most relevant to food and agriculture-related SDGs (e.g., SDG 2 “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture” and SDG 12 “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”), their activities and programs for members also cover other SDGs related to energy, climate, and social justice.

For example, the cooperative recently launched a program called ‘Climate Conversation at the Dining Table,’ which invites members to end ‘climate silence’ and share ideas and experiences about the topic of climate change with friends and family, as a way of normalizing and routinizing these conversations. Talking about the climate crisis more frequently can remind us of the severity and prevalence of the issue. In a similar vein, the cooperative encourages members to consider introducing more vegetarian dishes to their dining tables for healthy eating and a reduced carbon footprint. They feature Hansalim members’ simple and creative vegetarian recipes in their newsletter, blog, and social media. Also, the cooperative collects and recycles used containers of its products (e.g., glass jars and milk paper cartons) and incentivizes participants of this program with gifts or store credit for future use at local stores. The cooperative provides clear directions for how to clean and return used containers, for example, via its YouTube channel or social media platforms to promote these customer-engaging programs (Hansalim, 2015). As shown in Figure 3, its recent introduction of the ‘Bring Your Own Container’ section for grains is another effort to encourage customers to use fewer disposables and contribute to sustainable consumerism.

Figure 3: Hansalim stores offer less-packaging options with which customers can use their own containers for items sold by weight (e.g., grains). Image by Joohee Lee.

As part of its mission to provide customers with environmentally and socially sustainable products, the organization also supports grassroots activities like anti-GMO and anti-nuclear power generation movements. For instance, the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident strongly motivated the cooperative to introduce a rigorous self-inspection system for the radiation level of their items and to oppose the Korean government’s expansion of nuclear power generation. Instead, the organization advocates for localized and small-scale energy projects that promote energy conservation and replacement of carbon-intensive and high-risk energy systems with renewable ones. In 2012, the Hansalim community created a solar energy cooperative, called Hansalim Sunlight Generation Cooperative, separately to fund the installation of solar PV systems on Hansalim’s facilities. This energy cooperative also provides energy-related educational programs to local communities and sends sustainable energy items, like solar lanterns, to energy-vulnerable communities abroad.

Another interesting project of Hansalim beyond food-related issues is clothing recycling for socio-environmental causes. Every year, they resell used clothing donated by customers and redirect the sales revenue to at-risk neighborhoods in Korea and beyond (e.g., financial support for local schools in Karachi, Pakistan). Since the launch of this program in 2017, the cooperative has collected 560 tons of clothing in total, which is equivalent to reducing greenhouse gases by 3,500 tons (Hansalim, n.d.b).

Limits and Future Opportunities

Hansalim programs could be further developed and promoted for broader participation of the public living in urban areas. An especially important problem is that not all customers are fully aware of Hansalim’s grassroots activities and projects for food-climate-energy sustainability. In the future, the cooperative can consider increasing the visibility of these efforts by implementing creative advertisement strategies and learning from best practices done by similar cooperatives in other countries. In addition, Hansalim should continue its support program for visitors from other countries, especially developing economies, who visit them to learn successful programs and organizational strategies for application in their cultural and societal contexts.

In 2021, the cooperative’s research unit, the Moshim and Salim Institute, published a book about the Hansalim movement in English for those interested in the organization’s history and vision beyond the boundaries of South Korea (Hansalim, 2021). Hansalim Manifesto is an English translation of the book originally released in 1989 in the Korean language that invited readers to rethink the long-term effects of industrial civilization and technological society on humanity and ecosystems. Continued endeavors to connect with global communities by sharing the organization’s experiments and lessons are highly suggested. In the same vein, interacting and collaborating with similar organizations in other countries can allow Hansalim to learn different perspectives on food sustainability and continue to expand its vision for everyday food-climate-energy justice.

References

Choi, H. (2009). Institutionalization of trust as response to globalization: The case of consumer cooperatives in South Korea. Transition Studies Review, 16(2), 450-461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11300-009-0082-1.

Hansalim (2021). Hansalim Manifesto (In English). Available at http://www.mosim.or.kr/arc_list/3946?ckattempt=1.

Hansalim. (2018). Hansalim Story: Together Again and Fresher (In English). Available at https://issuu.com/7307/docs/2018______________-______.

Hansalim. (2015). YouTube Video on “How to Recycle Hansalim Glass Jars” (In Korean). Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwy_6i1yfaE&t=2s.

Hansalim. (n.d.a) About Hansalim (In Korean). https://shop.hansalim.or.kr/shopping/worldmeal/introduce.do.

Hansalim. (n.d.b). Hansalim Clothing Recycling: Achievements (In Korean). Available at https://hansalimotsalim.modoo.at/?link=eoi0ud2q.

Hansalim. (2016). The 30th anniversary of Hansalim: Growth from 1,500 to 600,000 member households (In Korean). Available at https://m.blog.naver.com/PostView.naver?isHttpsRedirect=true&blogId=hansalim&logNo=220880021217.

Kim, S., Lee, Y., Shin, H., & Jang, S. (2020). Chapter 20: Korea’s consumer cooperatives and civil society: the cases of iCOOP and Hansalim. In Waking the Asian Pacific Co-Operative Potential (pp. 225-233). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816666-6.00020-3.

One World Award. (n.d.). The Korean Hansalim Federation One World Award Gold 2014 (In English). Available at https://www.one-world-award.com/hansalim-korea.html.

Pak, M. S., & Kim, J. (2016). Ecophilosophy in modern East Asia: The case of Hansalim in South Korea. Problemy Ekorozwoju–Problems of Sustainable Development, 11(1), 15-22. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2830453.

Suh, J. (2015). Communitarian cooperative organic rice farming in Hongdong District, South Korea. Journal of Rural Studies, 37, 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.009.