Occupy Goes Global!

Quito

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Quito.

Scroll for more

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Quito.

Scroll for more

José Mena

Click the document icon to see this creative story

José Mena

Image 1: José Mena, Founder of MiHAoUZ, in the first prototype, image with permission to use by MiHAoUZ

Where is this grassroots initiative implemented? Who are the promoters? Who are the

beneficiaries?

Nestled in the heart of Quito, Ecuador, the MiHAoUZ Project isn’t just a concept on paper – it’s a testament to human ingenuity and the pursuit of a better tomorrow. With a vision rooted in creating thriving and self-sustaining communities across Ecuador, this personal initiative goes beyond blueprints and diagrams. It’s about turning dreams into reality through the power of prefabricated constructions that marry efficiency, affordability, and a light ecological footprint.

The project’s journey was fueled by curiosity and a commitment to transformation. Drawing inspiration from the bustling cities of Boston and New York, research was meticulously undertaken to distill concepts that could transcend borders and cultures. The result? A visionary blueprint for transportable, ecological, and replicable homes that could redefine the very essence of housing.

In 2016, the project stepped into the spotlight at the Entrepreneurship Fair of the esteemed San Francisco University (USFQ). Amid a sea of ideas, the MiHAoUZ prototype emerged as the undisputed victor in the Social and Environmental Responsibility category. This recognition was more than just a trophy; it was a testament to the project’s potential to reshape the narrative of responsible architecture.

But MiHAoUZ was not a lone crusader. It stood on the shoulders of local industries that believed in its cause. Cutting-edge materials flowed in from companies like NOVOPAN, KUBIEC, and Edesa, weaving innovation into every fiber of the project’s being. Financial support from INSOTEC breathed life into blueprints, ensuring that the vision was backed by more than just good intentions.

The heartbeat of MiHAoUZ resonated within the walls of the USFQ, where eager students, dedicated professors, and intrigued visitors converged to witness something remarkable. A community came together to see the prototype materialize before their eyes, transcending paper sketches and becoming a tangible testament to what collaboration can achieve. As the pieces fell into place, the structure rose from the ground in a mere day, a testament to efficiency and purpose.

Image 2: Speed Build: Prefabricated Home Assembly in 1 Day – MiHAoUZ Project, images with permission to use by MiHAoUZ.

How does this initiative engage with climate? Does it tackle mitigation, adaptation, both or other dimensions of climate change?

The heart and soul of the MiHAoUZ Project, however, lay in its outreach to the marginalized. It was a whisper of promise to rural communities that lacked the luxuries many take for granted – access to energy, sanitation, and dignity. These communities, often overlooked by progress, were the true beneficiaries of this endeavor. Solar panels and biodigesters replaced distant dreams with immediate solutions, channeling sustainable energy and hope into homes that stood as more than just structures.

The MiHAoUZ project proposes a shift away from traditional construction, which can have a significant impact on climate change due to several factors:

These prefab marvels weren’t merely about brick and mortar. They were bridges connecting people to the future they deserved, promising a better quality of life while treading lightly on the Earth. It was a quiet revolution, a way of saying that everyone deserves access to not just the basics, but to a life filled with respect for the environment.

MiHAoUZ wasn’t just about houses; it was about justice – environmental justice. It championed the spirit of innovation and the symphony of collaboration as it etched a path towards a brighter future. By redefining housing as not just a roof, but a promise, it unfurled the banner of change and cast a spotlight on a more equitable Ecuador. It was a beacon, a reminder that the future could be built with intention, compassion, and a deep understanding of what it truly means to uplift communities while treading gently on the Earth.

What are the main objectives? What are the main values?

In the heart of Ecuador’s rural landscapes, the MiHAoUZ project comes alive with a fervent mission to weave together the fabric of sustainable communities. At its core, this endeavor is more than just a blueprint – it’s a heartfelt journey towards harmonizing humanity with the environment.

The main objectives of the MiHAoUZ project are: (1) creating sustainable communities, (2) reducing environmental impact, (3) promoting replicable solutions.

Imagine walking through the verdant landscapes of Ecuador’s low-income rural areas, where hopes and aspirations are often overshadowed by the lack of affordable and eco-friendly housing. This is where MiHAoUZ steps in, with a resolute determination to craft something extraordinary out of the ordinary. It envisions communities that are not just clusters of houses, but thriving ecosystems where families can flourish.

One of MiHAoUZ’s pillars is its commitment to creating homes that are more than shelter – they’re catalysts for transformation. These homes will stand as living testaments to resilience and innovation. They will harness the power of the sun with solar panels that wink in the daylight, generating clean energy for the community. Waste will turn into wealth as biodigesters transform organic matter into valuable resources, creating a circle of sustainability that mirrors the rhythms of the Earth itself.

The project doesn’t just build structures; it crafts narratives of change, stories of people taking the reins of their own lives. With every nail hammered and every beam laid, the community becomes the author of its own destiny, shaping the physical and social landscapes for generations to come.

But MiHAoUZ doesn’t stop at erecting homes. It’s a movement, a revolutionary dance with the environment. It’s about using prefabricated materials that whisper secrets of efficiency, and innovative building techniques that embrace the future while honoring the past. As hammers meet nails and walls rise to meet the sky, the project pays homage to the Earth by reducing waste and energy consumption, casting a vote for sustainability and climate resilience.

At its heart, MiHAoUZ is a storyteller. It doesn’t just tell one tale; it pens a multitude. It doesn’t just build one home; it lays the foundation for countless more. The project’s beating heart is woven with threads of sustainability, social responsibility, innovation, and collaboration – values that infuse every step, every decision, and every dream.

With each brick laid, the project stands as a tribute to social responsibility. It’s a gesture of solidarity with those whose voices often go unheard – the marginalized, the underserved. MiHAoUZ isn’t just about building structures; it’s about weaving dreams and aspirations into the very fabric of these communities, providing a sanctuary where futures can bloom.

Innovation is the song that MiHAoUZ sings. It’s the tune of possibility, the melody of progress. As new materials and technologies are woven into the architectural tapestry, these homes become living embodiments of creativity and forward thinking. Aesthetic marvels that blend seamlessly with their surroundings, these homes are a testament to the power of human imagination to harmonize with the natural world.

Collaboration is the symphony that propels MiHAoUZ forward. It’s a harmony of minds and hearts, a collective endeavor that embraces the knowledge of local industries, the backing of financial institutions, and the wisdom of academic partners like USFQ. Together, they breathe life into MiHAoUZ, transforming it from a vision into reality.

In the story of MiHAoUZ, the past and the future merge, creating a narrative that transcends time. It’s a tale of sustainable homes rising from the Earth, of communities standing strong against the tides of change, and of a world that becomes a little more just and equitable with every brick laid. As MiHAoUZ turns the page on conventional housing, it pens a chapter of hope, resilience, and transformation – a chapter that will be read and remembered for generations to come.

What is the timeline? Are there already visible effects?

Over the course of its journey, the MiHAoUZ Project has woven a tapestry of experiences that breathe life into its aspirations. The initial prototype, a testament to innovation, was painstakingly transported and reassembled on Ilaló Hill not just once, but thrice, underlining the persistence and determination that lie at the heart of this endeavor. From this humble genesis, the project’s scope expanded to encompass diverse locales, each with its own story to tell.

A significant chapter unfurled in the historic city of Ambato, nestled 150 kilometers away from the bustling heart of Quito. Here, the project gained recognition beyond its innovative construction techniques, breathing life into the very essence of the city’s architecture. The mantle of transformation then extended to Tumbaco, a quiet suburb where the construction of two houses mirrored the dreams of countless families seeking sustainable shelter. In this microcosm, the project’s foundations stood as a beacon of hope, embodying the belief that a brighter future could be built one brick at a time.

A symphony of impact echoed through the creation of a school, an amalgamation of nine interconnected buildings in the backdrop of progress. The community’s children embarked on a new chapter, where the structures that housed knowledge were themselves a testament to the harmonious coexistence between human habitats and the environment.

And as the project’s reach stretched even further, the sands of Olón, a tranquil coastal retreat, bore witness to its transformative touch. Here, a house emerged as more than just bricks and mortar; it was a testament to the adaptability of the project to diverse terrains and climates, standing as a sentinel against the tide of conventional construction practices.

Figure 1: Chronicle of Innovation: The Evolution of the MiHAoUZ Project, images with permission to use by MiHAoUZ

Through these unfolding stories, the very tenets of the MiHAoUZ Project were tested, and they stood strong, like the pillars of a bridge connecting innovation and reality. The chapters of this tale, etched in time, resonate with meaning:

Who are the actors involved? What are their backgrounds?

These experiences, etched on the canvas of time, illuminate the project’s effectiveness in ways mere words cannot capture. The whispers of swift assembly, the tales of translocation, the echoes of repetition, and the embrace of adaptation together form a narrative that attests to the MiHAoUZ Project’s impact. It stands as a living testament to the fusion of sustainability and community, reducing the footprint of the past while laying the foundation for a greener future.

Amidst these pages, the characters who breathe life into this narrative emerge, each with a unique role and story:

By bringing together industries with forest assets, professionals from academia, local governments, and communities, the MiHAoUZ project creates a collaborative and multi-stakeholder approach. Each actor contributes their unique background and expertise, ensuring the project’s success in delivering sustainable and environmentally friendly housing solutions to low-income rural communities.

Thus, the MiHAoUZ Project isn’t a mere abstract concept; it’s a living tapestry woven by a cast as diverse as the colors of nature. It’s a tale that captures the human spirit’s capacity to bridge dreams and reality, to create harmony between innovation and the world we call home.

Figure 2: Harmonizing Rural-Urban Ecology: A Holistic System Approach, figure with permission to use by MiHAoUZ

Which limits does it encounter?

MiHAoUZ is a project driven by a noble mission to uplift rural communities through sustainable housing solutions. However, like any entrepreneurship, it faces a range of real-world challenges that require more than just a conceptual approach. Let’s delve into the project’s challenges and potential hurdles with more depth, recognizing the human factors at play:

Are any shortcomings or critical points visible? What other problematic issues can arise from its implementation?

In this journey to make a difference, there are people behind every challenge:

How would it be potentially replicable in other settings?

The MiHAoUZ project is more than just a blueprint; it’s a living example of adaptable and sustainable housing that resonates with the real world. Here’s a deeper look at how its replicability is firmly grounded in practicality and human engagement:

Crafting Homes with a Human Touch: The heart of the MiHAoUZ project beats with the concept of adaptable design. Think of it as a puzzle that clicks together to form a cozy, modern home. The beauty is that this puzzle can be assembled in various corners of the world, addressing unique needs and cultures. Each modular piece is like a brushstroke in a masterpiece painting, with local materials and techniques adding vibrant shades to the canvas. The project’s genius lies in being able to embrace the landscape, climate, and the people who’ll inhabit these homes.

Sustainability that Sings: The MiHAoUZ project is not a sterile prototype, but a testament to sustainable living. It’s a whisper to the environment, a promise to minimize the carbon footprint. Wood and renewable resources are the orchestra, playing harmoniously with solar panels and biodigesters. As the sun kisses the solar panels, and waste transforms into energy, it’s more than a home; it’s a symphony of ecological harmony. This harmony can be the anthem for other communities, echoing through homes built with respect for the planet.

Communities Building Communities: Imagine a village coming together to build its future. The MiHAoUZ project is more than construction; it’s a collective endeavor. It’s a celebration of culture and identity, with local communities adding the brushstrokes to the canvas. The very process of building these homes cultivates a spirit of collaboration. From young hands passing tools to elders sharing wisdom, the MiHAoUZ project isn’t just about erecting walls; it’s about nurturing bonds and shared dreams.

Redefining Shelter: When winds howl and earth trembles, MiHAoUZ houses stand firm – not as mere structures, but as shields of resilience. These homes are woven from threads of preparedness. With their roots in sustainable building practices, they empower communities to face nature’s fury with courage. It’s more than shelter; it’s security. And this security ripples through the community, encouraging the preparedness that safeguards lives and dreams.

From Local to Global: MiHAoUZ doesn’t just build houses; it constructs a better world, brick by brick. Its impact extends beyond four walls – it’s about the systems that govern our lives. As policy makers witness the triumphs of the project, they’re nudged towards a fresh perspective. Regulations and incentives blossom, nurturing eco-friendly practices. The MiHAoUZ initiative serves as a storyteller, spinning narratives of change that inspire broader shifts in the way we build and live.

Empowering Tomorrow: MiHAoUZ empowers communities by giving them more than a home; it gives them agency. It’s a catalyst for change – not just in architecture, but in how we perceive the power of community. As the MiHAoUZ project spreads its wings, the lessons learned become a compass for others to navigate their own journeys. It’s a ripple that extends far beyond construction, carrying the spirit of sustainability, resilience, and empowerment to new horizons.

In Conclusion: The MiHAoUZ project isn’t just about replicating structures; it’s about replicating ideas, dreams, and hope. It’s about embracing the pulse of a community, the heartbeat of a planet, and weaving them together into a tapestry of sustainable living. From modular components to resilient communities, from local adaptations to global shifts – the MiHAoUZ initiative is an anthem for a more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient world.

Is this initiative conducive to broader changes?

Yes, the MiHAoUZ initiative has the potential to contribute to broader changes in various areas, fostering long-term sustainability, community preparedness, and influencing institutional arrangements. Here are some ways in which the project can facilitate broader changes:

Legal and institutional frameworks: The success and impact of the MiHAoUZ project can highlight the need for updating or creating supportive legal and institutional frameworks. It can demonstrate the effectiveness of sustainable construction practices and encourage policymakers to develop regulations and incentives that promote eco-friendly and resilient building methods.

Community preparedness: By implementing sustainable and resilient housing solutions, the MiHAoUZ project can enhance community preparedness for natural disasters, such as earthquakes or extreme weather events. The project’s focus on safe and adaptable housing can encourage communities to prioritize disaster preparedness, fostering a culture of resilience and proactive measures to mitigate risks.

Long-term sustainability: The MiHAoUZ project’s emphasis on sustainable materials, energy efficiency, and low-carbon design aligns with the goals of long-term sustainability. By showcasing the benefits and feasibility of sustainable construction practices, the initiative can contribute to a shift towards more environmentally conscious building methods in the construction industry.

Community empowerment: Through its participatory approach, the MiHAoUZ project empowers communities by involving them in the decision-making process and providing them with sustainable housing solutions. This empowerment can extend beyond housing, encouraging communities to actively engage in other aspects of sustainability, such as resource management, renewable energy adoption, and social cohesion.

Knowledge dissemination and replication: The MiHAoUZ project can serve as a valuable case study and knowledge hub for sustainable construction practices. By sharing their experiences, best practices, and lessons learned, the project can inspire and inform other initiatives, leading to a wider adoption of sustainable building methods and contributing to broader changes in the construction sector.

Overall, the MiHAoUZ initiative has the potential to catalyze broader changes in law, institutional arrangements, long-term sustainability practices, community preparedness, and community empowerment. By showcasing the benefits of sustainable and resilient housing, the project can contribute to a more sustainable and resilient future in both local and global contexts.

References

Earth Overshoot Day home – #MoveTheDate. (n.d.). Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.overshootday.org/

Español — IPCC. (n.d.). Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.ipcc.ch/languages-2/spanish/

Este proyecto crea vivienda inteligente y transportable | Revista Líderes. (n.d.). Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.revistalideres.ec/lideres/proyecto-vivienda-inteligente-transportable-desarollo.html

Post Occupancy Evaluations | WBDG – Whole Building Design Guide. (n.d.). Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.wbdg.org/resources/post-occupancy-evaluations

Pamela Salome Chavez Calapaqui

Where is this grassroots initiative implemented? Who are the promoters? Who are the beneficiaries?

This grassroots initiative is being implemented in the city of Quito, Ecuador. The main neighborhoods that Yanapana is working with are in the Chillogallo parish. This is in the peri-urban area, where the houses are constructed on the hillside (which means they are located in a zone prone to risk). Their population doesn’t have full access to basic services and equipment. These neighborhoods are: La Dolores and Cumbres del Sur.

Yanapana´s promoters are four young people who launched this initiative in July 2020. They work together with 60 volunteers approximately, plus the allies that support the cause with donations. One of its allies, the De Base organization, works in the field closely with these neighborhoods. Other allies that Yanapana works with are the civil organization Love is Giving and the AMS club Ecuadorian Students Association (ESA) of the University of British Columbia.

The beneficiaries are the families who live in La Dolores and Cumbres del Sur. Currently, Yanapana is working in a tailored plan with only 2 families of these neighborhoods.

The Name Yanapana comes from the Ecuadorian language kichwa, and means “to help a friend”. Yana means help and pana means friend.

How does this initiative engage with climate? Does it tackle mitigation, adaptation, both or other dimensions of climate change?

Yanapana’s aim to construct urban orchards in the neighborhoods of La Dolores and Cumbres del Sur constitutesa mitigation practice against climate change, as well as an adaptation practice.

It is a mitigation practice in the sense that the implementation of urban orchards will permit the reduction of greenhouse gases emission through different methods. The harvest of organic products obtained from the community orchard will reduce the consumption habits of inhabitants and therefore the amount of plastic they use. There will also be a significant reduction in the commute distances to supply themselves with food. In addition, urban orchards help reduce the accumulation of C02 and heat in cities, allowing to alleviate the consequences of heat islands. Moreover, urban orchards promote the production of compost from organic household waste, which also helps in the reduction of greenhouse gases.

Yanapana also embraces adaptation practices in order to tackle climate change. It seeks to adapt human behaviour through the change in consumption and feeding practices. This grassroots movement tries to offer people the opportunity and the resources to empower themselves and change the consumer dynamics of the modern world. By adjusting their ways of food production and consumption, this organization is opening the possibility for other neighborhoods to adapt these practices to their daily lives.

What are the main objectives? What are the main values?

Yanapana originates from values of love and solidarity with the purpose of providing the foundational nourishment for the body and mind of children. Its main values are solidarity, honesty, cooperation, responsibility and service. Its mission is to tackle the malnutrition problem within vulnerable groups of Ecuador through education, solidarity, and international cooperation; so that every person gets the opportunity to nurture their body, mind and spirit.

The main objective of this initiative is to combat malnutrition in vulnerable groups living in poverty. Yanapana’s target group are families with children under the age of five, as well as families with pregnant women or in lactation period. However, their work is not limited to these groups. The organization delivers food baskets to the beneficiary families and works closely with them to empower their abilities and improve their living conditions and feeding habits in a sustainable and self-sustaining way.

The organization provides the necessary tools and resources for the urban gardens to be built, including educating the population with workshops and specialised training in urban agriculture. To make this possible, the initiative is planning to make alliances with organizations like Agrupar- Conquito andthe Guardianes de las Semillas.

Once the urban orchards are built, families will be taught about healthy nutrition habits based on nutritional plans that will include the orchards’ products. This movement also aspires to involve children and adolescents in the urban orchards activities, with the purpose of letting them explore agriculture as in a farm school. Finally, the long term purpose is to generate micro-enterprises (owned and managed by the families) from the harvested products.

What is the timeline? Are there already visible effects?

Yanapana was born on the 26th of July 2020. This grassroots movement was created in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. After one year and a month of operation, it has achieved important steps towards its final objective. In this period of time, alliances were established with the organization De Base and the civil group Love is Giving. During this time, food baskets have been delivered to the most vulnerable families.

Together with the movement De Base, Yanapana is working on the first communitary orchard in La Dolores neighborhood. The first sowing was the 10th of October 2021. In the long term, Yanapana is looking to construct a second urban orchard in Cumbres del Sur neighborhood. In addition, in one or two years, Yanapana aspires to develop micro-enterprises owned by the beneficiary families.

Who are the actors involved? What is their background?

The founders have just graduated from university in the midst of the pandemic. Amid all the chaos, they saw an opportunity to use the resources everyone had available as recent graduates to create positive change in their community.Then, as a group, they came up with this project.

Which limits (institutional, physical, social, etc.) does it encounter?

The movement’s principal limits have been economical. Because this grassroot movement began almost one year ago, it has been really difficult for their founders to obtain the necessary monetary funds for the construction of urban gardens. At the beginning, it was also difficult to capture visibility, that is, to be known by other movements or organizations with more experience and extensive contact networks in the city and the country. Yanapana has not yet achieved such visibility. However, it seeks to achieve greater recognition and therefore more opportunities to expand the project’s cause.

Are any shortcomings or critical points visible? What other problematic issues can arise from its implementation?

One of the main shortcomings faced by the initiative is the dependence it has on donations and alliances for the implementation of the initiative. This is a bit problematic since it does not have yet the capacity to self-finance its work, risking to lose part of their income in the process, and thus altering the continuation of the orchards project. Furthermore, another shortcoming is the fact that it is highly difficult to produce a permanent impact on people’s behaviour, which means that the work with beneficiaries should be comprehensive enough to inspire them in a new lifestyle.

How would it be potentially replicable in other settings?

Quito is a city with a great number of precarious neighborhoods situated in the peripheries. There are similar neighborhoods to La Dolores and Cumbres del Sur in the south and north of Quito that have enough space to manage the construction of urban orchards. Even next to La Dolores, there is another neighborhood with similar conditions, the 9 de Diciembre neighborhood. Therefore, the possibility to replicate this initiative is achievable.

Is this initiative conducive to broader changes (law, institutional arrangements, long-term sustainability or community preparedness, etc.)? If yes, which?

This initiative seeks to lead to broader changes. The project aspires to produce long term sustainability through the work made in close relationship with beneficiaries. This close relationship permits to provide the beneficiaries with the necessary tools for acquiring more sustainable feeding habits, less consumer practices and a greater desire to live in community. In general, the initiative plans to prepare the community to live in a more sustainable and self-sustaining way, in harmony with people and nature.

.

Links for knowing more about Yanapana Project:

Instagram:https://www.instagram.com/yanapana_project/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/YanapanaProject

Website:https://es.yanapanaproject.org/

References:

Interview with member of Yanapana Project Foundation

Google. s.f. Google Maps location of Quito. Retrieved October 15, 2021 from https://goo.gl/maps/JytRkixc3psZCMoB7

Google. s.f. Google Maps location of La Dolores and Cumbres del Sur neighborhoods. Retrieved October 15, 2021 from https://goo.gl/maps/GksmPqVEZegGz3RYA

Yanapana Project Foundation s.f. Retrieved October 15, 2021 from https://es.yanapanaproject.org/

Kyra Torres

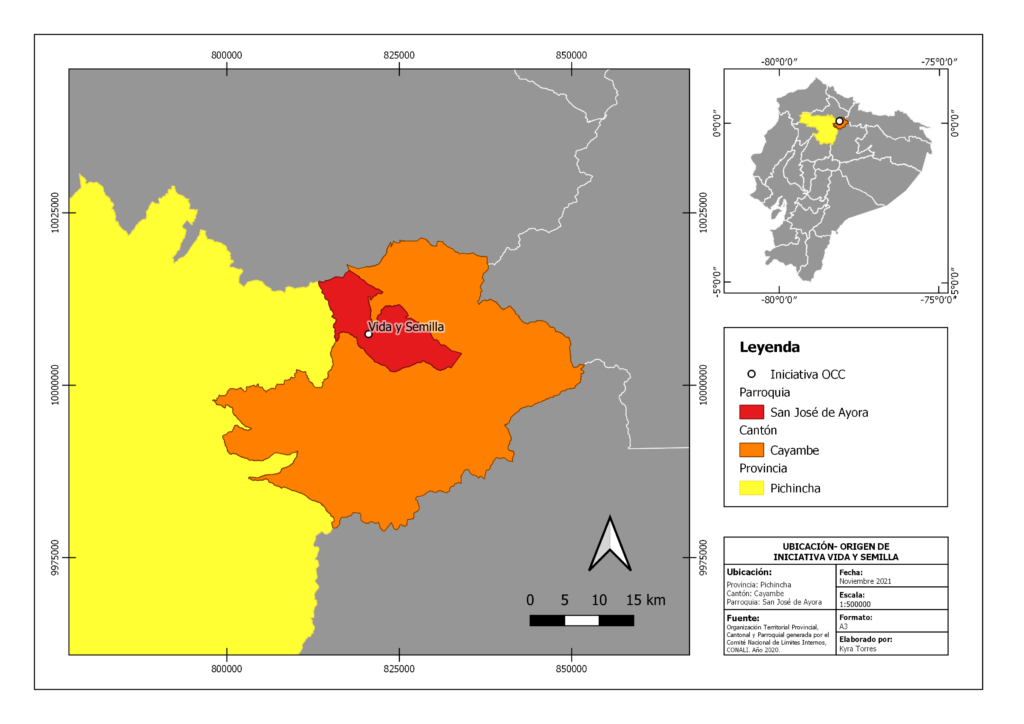

Where has this grassroots initiative been implemented? Who are the promoters? Who are the beneficiaries?

The organization arises as a personal initiative in the San José de Ayora parish, Cayambe canton, Pichincha province, Ecuador. Vida y Semilla works closely with people from Quito, the country’s capital, and different parishes within Pichincha. Its founder is Isabel Sánchez, and her family is her support and inspiration in this endeavor that currently includes the participation of 12 people (Sánchez, interview, 2021).

The association has several undertakings, including training and provisioning to produce and consume food in a local, healthy and responsible way (Quito Informa 2017). Relevant work has been carried out in the recovery of traditional knowledge and the training of seed guardians. Urban and rural populations in the province have significantly been influenced. They have gained access to diverse organic seeds, including edible, medicinal and ornamental plants, and knowledge of their cultivation, harvesting, and consumption.

How does this initiative engage with climate? Does it tackle mitigation, adaptation, both or other dimensions of climate change?

Food increasingly travels greater distances from its origin to the consumer. Agroindustrial production processes, processing cycles, packaging, upkeep, distribution costs, and the waste generated require large amounts of energy that come primarily from fossil fuels (Mediavilla 2013, Crippa et al. 2021).

As Mediavilla points out, “the case of food is paradigmatic since it is estimated that it travels an average of 4,000 kilometers before reaching our table, when a large part of it can be produced nearby”[Translated from Spanish] (2013, 206). Thus, a third of global energy consumption and consequent carbon emissions are caused by the current agribusiness model that has shown to have lower energy efficiency per calorie produced when compared to the previous century (Mediavilla 2013).

Human influence on the recent alterations of the climate system is unequivocal, and greenhouse gases have been recognized as part of the main anthropic factors of climate change at a global level (IPCC 2021). The agri-food industry has become one of the biggest polluters, with solid contributions to the emission of greenhouse gases.

In 2015, GHG emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, fluorinated gases, amongst others) from the agri-food system represented 34% of total global emissions (Crippa et al., 2021). As Crippa and his colleagues note, “the largest contribution came from agriculture and land use/land-use change activities (71%), with the remaining were from supply chain activities: retail, transport, consumption, fuel production, waste management, industrial processes and packaging” (2021, sn).

Climate change, in addition to the increase in global temperature, represents a series of risks for food production, such as the intensification of extreme climatic events, droughts, frosts, heat waves, floods-, alteration of rainfall cycles, increase in sea level, loss of glaciers, impact on freshwater sources, amongst others (IPCC 2015, 2021).

The production and quality of food, livelihoods, and public health in Latin America are especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (IPCC 2014). Similarly, the global south countries are increasingly exporting better quality calories at low cost and importing expensive poorer calories, which have hurt the diet quality of the most vulnerable Ecuadorian households (Falconí 2002) and have influenced the persistence of distributive conflicts and inequity.

The organization encourages sustainable food production, promoting local, ecological, circular, and healthy production and consumption through the education and distribution of organic seeds. This, if replicated on a larger scale, would increase the energy efficiency of the agricultural output and reduce GHG emissions resulting from the agri-food system production chain.

It is also relevant that the recovery of native plant seeds has a more efficient production, and also protects the diversity of Andean plant species and favors wild pollinator’s reproduction. Since the species are adapted to local climates and realities, less energy is invested in their production, and the consumption of resources, such as water, fertilizers, and pesticides, is reduced.

What are the main objectives? What are the fundamental values?

Isabel (personal comments, 2021) states that Vida y Semilla has the following aims:

-Rescue native seeds together with ancestral knowledge and agricultural practices that entail their management and reproduction;

-Educate people and groups about circular economies, 0 km production, food sovereignty, nutrition, among other related topics;

-Work with children, understanding their potential and the need to adapt to the potential challenges of the future ecological and climatic crises that lie ahead;

-Motivate people to produce their own food and consume locally, efficiently and responsibly.

What is the timeline? Are there any visible effects already?

In 2008 Vida y Semilla was born commercially. In 2010 the initiative joined the Red de Guardianes de Semillas (Seed Guardians Network), a group of organizations that aim to protect agrobiodiversity and promote regenerative life systems in Ecuador, emphasizing the social and educational part of food production. In 2017 Isabel was the winner of the “Successful Entrepreneurship” Program promoted by ConQuito (Quito Informa 2017). With this, the association expanded to include 12 people who seek, in addition to the production of seeds, to educate and train new guardians.

Currently, the association continues to work with more than a hundred native species of organic seeds for food production, ecosystem recovery and reforestation, diffusion of plant species for pollinators, production of seeds for sprouts, citizen education and training processes, amongst other actions that has become their alternative of life and economic sustenance. Additionally, it should be remarked that they protect 80 types of cultivated native seeds (Sánchez, interview, 2021).

What advocates are involved? What is their background?

The key stakeholder in this initiative is Isabel Sánchez, who, as a child, helped her grandmother, Isabel Calderón, in the collection, classification, and handling of seeds for agriculture. Her grandmother instilled this interest and transmitted the traditional knowledge orally, as a part of everyday life, to her family.

Later, the organization’s founder studied biology and continued to work in seed production, establishing a dialogue between ancestral and formal-academic knowledge. Her family members participate in the initiative, with exceptional support from her husband, Ricardo Cabezas, and her cousin, Natalia Lascano.

The work has slowly spread and gained the recognition of entities such as the Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito and ConQuito. Due to the restrictions placed under the COVID 19 Pandemic, many people in the city of Quito and surrounding valleys realized the importance of local food production, which has driven the work of the last year and has expanded its influence in urban areas (Sánchez, interview, 2021).

What limiting factors (institutional, physical, social, etc.) does it encounter? ∙ Are any shortcomings or critical points highlighted? What other problematic issues can arise from its implementation?

Isabel would say that the toughest challenge is to compete in the market with hybrid and transgenic seeds, whose production costs are lower, in a socioeconomic reality where the price can make local and responsible projects challenging to access for the most vulnerable communities.

The reduced number of opportunities for the commercialization and exchange of this type of products and little space for the socialization of these initiatives, which bring producers and consumers closer together, is also precise.

Finally, there is evidence of a lack of education and recognition that prevents more significant support and dissemination of the principles that move Vida y Semilla.

How could it conceivably be reproduced in other settings?

The initiative can be replicated at different scales and geographic spaces. It is considered of particular relevance in those places where there is traditional agricultural knowledge that must be recovered and transmitted to future generations. Similarly, it could be replicated in those places where the cultivation of native species is being lost due to the use of GM seeds.

Education is a fundamental pillar for the construction and dissemination of alternative models of local production and consumption by being more energy-efficient, which in turn reduces pollution throughout the production chain.

Another way to replicate the proposal is through the creation of networks, not only at the local level but also regionally and even globally, where experiences and knowledge can be shared, actions made visible, external funds can be obtained to potentiate ventures and thus counter the agroindustrial model that is outcompeting small producers.

Is this initiative conducive to broader changes (law, institutional arrangements, long-term sustainability or community preparedness, etc.)? If yes, which?

By achieving a greater scale and dissemination, this initiative proposes giving rise to a more sustainable food production and consumption model. In countries like Ecuador, which, due to their biophysical characteristics, allow a rich and varied local production, the risk posed by climate change for food sovereignty and security could be mitigated, improving nutrition and quality of diet.

The consumption of local products and even the organization and mobilization in favor of urban cultivation would also help reduce GHG emissions associated with the very high levels of energy consumption required by industrial food production and the great distances they travel to consumer tables.

References

Crippa, Monica, Efisio Solazzo, Diego Guizzardi, Fabio Monforti, Francesco Tubiello, Adrian Leip. 2021. “Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions.” Nature Food 2: 1-12. Doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9.

Falconí, Fander. 2002. Economía y Desarrollo Sostenible ¿Matrimonio feliz o divorcio anunciado? El caso de Ecuador. Quito: FLACSO Ecuador.

IPCC, Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. 2014. El Quinto Reporte de Evaluación del IPCC ¿Qué implica para Latinoamérica? Resumen Ejecutivo. Alianza Clima y Desarrollo.

IPCC, Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

Mediavilla, Margarita. 2013. “¿Cómo ha de producirse la transición a un modelo energético sostenible?”. Documentación social 167: 191-211.

Quito Informa. 2017. Emprendedores en la agenda internacional: A un año de Hábitat III. Disponible en: http://www.quitoinforma.gob.ec/2017/10/20/emprendedores-en-la-agenda-internacional-a-un-ano-de-habitat-iii/. Consultado el: 3 de junio de 2021.

Sánchez, Isabel. 21 de junio de 2021. Entrevista virtual. [Plataforma Google Meets]. Quito.

Social Networks:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Vida-y-Semilla-253067625121807

Grace López Realpe

Natura Insurrecta (NI) is a self-managed ecological organization located in Quito. It belongs to Bloque Proletario, which is a Popular Front Movement that brings together various organizations of workers, peasants, students, women, artists, popular neighborhoods, and aims to develop a new revolutionary current in Ecuador. NI was formed in 2016 to face social and environmental issues from a materialistic position through ecological, social, and economic analysis. Given the strong impact generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020 they built three urban community orchards in the peri-urban area of Quito, at Zabala-Calderón, the Commune of Sorialoma in Guangopolo, and San Francisco de Miravalle (Figure 1). In cooperation with local communities, they have opened spaces to work the land with two objectives:

NI works together with other organizations from Bloque Proletario such as Luna Roja, which defends women’s rights; ASOTRAB, which organizes non-regulated street vendors and sexual workers; and La Pobla, which works at neighborhoods and helps with the coordination of “community pots” at marginalized areas from Quito. The “community pots” is an initiative that consists of the collective preparation of food to face hunger in popular areas of Quito (Figure 2).

Urban farming activities play a mitigation role in climate change since they are green spaces in cities that act as carbon sinks.In addition, NI’s urban community orchards are managed in an agroecological manner, promoting sustainable agriculture that supports changes in food consumption patterns and enables the reduction of food transportation and storage, allowing a decrease in the use of fossil fuels. Composting practices are also developed, contributing to better management of organic waste.

Community orchards are also adaptation practices to climate change because they improve resilience by reducing the exposure and vulnerability to the lack of food, faced by people living in poor neighborhoods. Besides, through collective action to produce food, the community develops self-sufficiency and control over agricultural systems, allowing localized appropriation of production spaces, but also practices linked to caring for the environment at the local level, health care; all this outside of transnational companies or public policies as bodies that organize food production and consumption.

NI’s main principles are self-management, collective action, class independence, and free transfer of knowledge. They consider that nature problems are exacerbated by capitalism, thus to protect nature and the environment it is necessary to organize and come together between different oppressed sectors. NI acts from a radically popular view; their causes include the women’s rights movement, the fight against power and oppression, and the importance to develop a project free of institutions such as political parties and NGOs. Its purpose is to develop new paths of organizing to reach social and environmental justice. Community orchards are a means and not an end, to promote agency, political activation, understanding of reality, and raising awareness.

The processes developed at the orchards show that the changes and repairs to reduce the precariousness of life in the cities, and the destruction of nature, must take place at a collective level, not at an individual one.

Since its formation in 2016, it has carried out several initiatives such as annual political training schools, study circles, forums in universities, discussions, among others. The creation of urban orchards is a project framed in the work in neighborhoods that took shape in 2020, in the context of the global pandemic. In one year of operation, they have managed to harvest radishes, squash, tomatoes, corn, and more products that have been used in the cooking of “community pots”, aimed mainly at street vendors and other vulnerable populations. Moreover, at the Sorialoma Commune gardens, art workshops have been held with neighborhood children, guitar classes, painting, and welding (Figure 3). Between August and September 2021, an Ecological Political School was held on problems of nature and society. In the future, it is proposed to continue with work in neighborhoods and create programs to promote food sovereignty and improve the nutrition of the inhabitants of popular neighborhoods in Quito.

The actors involved in the organization are diverse, including students, workers, artists, researchers, teachers, and residents of the neighborhoods. In short, they are activists and an organized community that seek to combine their knowledge, between traditional and technical, to work the land in the orchards and generate necessary political reflections in these times. In Ecuador, national unemployment reached 13.3% of the Economically Active Population between May and June 2020, compared with 3.8% in December of 2019 (INEC 2020). The situation gets even worse for people living at the urban peripheries (Vega Solis & Bermúdez 2019). The orchards and “community pots” are a concrete response to face this difficult reality.

The two main limitations for the development of NI’s projects are funding and the levels of participation. Being a self-managed activity, the construction of community orchards has been sustained by volunteers’ work, such as minga[1], and by campaigns for the donation of tools and supplies done in social networks. Another way to collect funds is by preparing and selling food, and also offering paid workshops, for example, a Geographic Information Systems course was recently held. The orchards require constant work and unfortunately, participation is still sporadic. Of the 33 people registered as volunteers in the orchards, approximately half attend every weekend to work.

The activity is replicable, the orchards have expanded to three different areas of the city, and the work of the popular pots has spread among 10 peripheral neighborhoods in the north and south of Quito. As there are several vulnerable peri-urban areas in the city, work can continue to grow. However, to achieve this goal it is necessary to convene a greater number of participants committed to working on the land and promoting social transformation.

Natura Insurrecta has built community gardens from an environmental and social conscience, seeing them as a means for social transformation. As established by the founder of the organization:

(…) What we want to promote with the popular pots is to meet the needs of the people (…) But that is not the only purpose, we want to demonstrate to the people who are in the neighborhood, in the field, that by organizing ourselves collectively we can help each other” (Carlos, interview, 2021).

The urban community orchards developed by Natura Insurrecta in Quito are a demonstration that it is possible to generate broader changes at an urban scale regarding climate action and social justice. The sum of political action with collective work based on reciprocity practices becomes an organizational mechanism that improves people’s quality of life and support in the fight for the right to the city.

References

INEC – Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. 2020. “Encuesta Nacional de Empleo, Desempleo y Subempleo (ENEMDU)” Indicadores laborales mayo-junio 2020, 1-49.

Testori, G., & d’Auria, V. 2018. Autonomía and Cultural Co-Design. Exploring the Andean minga practice as a basis for enabling design processes. Strategic Design Research Journal, 11(2): 92-102. May-August. doi: 10.4013/sdrj.2018.112.05.

Vega Solis, C., & Bermúdez Lenis, H. F. 2019. Informalidad, emprendimiento y empoderamiento femenino. Economía popular y paradojas de la venta directa en el sur de Quito (Ecuador). Revista De Antropología Social, 28(2), 345-370. https://doi.org/10.5209/raso.65618.

For this entry, an in-depth interview was conducted with the founder of Natura Insurrecta, Carlos Realpe. Also, participatory action research was carried out in the different gardens created by NI.

Finally, information was collected from social networks of the organizations analyzed. And a documentary video on the orchard’s initiative was reviewed, found at the following link: https://www.facebook.com/1573339092681322/videos/2109568965845500

Facebook Frente Ecológico Natura Insurrecta:https://www.facebook.com/Frente-Ecol%C3%B3gico-Natura-Insurrecta-1573339092681322

Facebook La Pobla: https://www.facebook.com/lapoblaresiste

[1] It is a communal work practice from the Andean Region that is traditionally used for agricultural purposes between indigenous peoples. It has also spread among other social groups as a form of social, economic, and political organization. The minga is one of many systems of community work and reciprocity where people do not expect anything in return apart from collective benefit (Testori & d’Auria 2018).

Grace López Realpe, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO)

“We conserve and recover the water sources of the Metropolitan District of Quito”

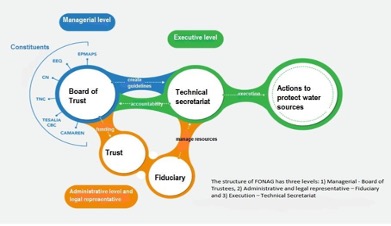

The Fund for the Protection of Water (FONAG) is “an alliance of people, institutions, and communities committed to the conservation and restoration of the water sources of the Metropolitan District of Quito (DMQ)” (FONAG 2019). It was created in 2000 through a Constitution Agreement between the Empresa Pública Municipal de Agua Potable (EPMAPS, the Municipal Sewer and Potable Water Company of Quito) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), as a private commercial trust with a useful life of 80 years and which is regulated by Ecuador’s Securities Market Law (FLACSO-PNUMA 2011).

FONAG’s mission is to protect the watersheds that supply water to the DMQ, working together with local stakeholders. In order to achieve its objective, it executes programs and projects of conservation, ecological restoration, and environmental education through a financial mechanism. In summary, the fund seeks to create “a new culture of water and integrated management of water resources” (FONAG, 2019). Other constituents of the trust, which subsequently joined, are Empresa Eléctrica Quito (EEQ, Electric Company), Cervecería Nacional (CN, National Brewery), Tesalia Springs CBC, and Consorcio de Capacitación en el Manejo de Los Recursos Naturales Renovables (CAMAREN, Renewable Natural Resources Management Training Consortium), which is part of the constituents of FONAG since 2010, because the Swiss Cooperation (COSUDE), a partner since 2005, transferred its contributions to the Consortium (FONAG 2019) (Figure 1).

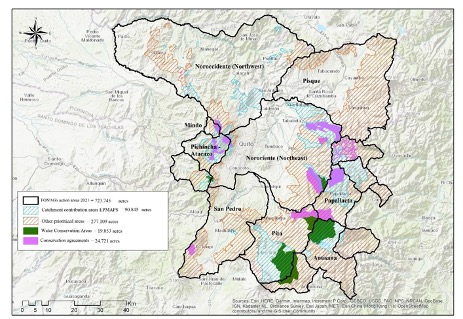

The trust works as an endowment fund which gets contributions from citizens through their payments to public companies and contributions from public and private institutions (FLACSO-PNUMA 2011). Currently, the contribution represents 2% of the fixed amount from sales of potable water and sewerage of the EPMAPS. This was established through Ordinance 213 (Concejo Metropolitano de Quito 2007). The remaining equity of the trust corresponds to annual fixed amounts paid by the other constituents. The equity returns are used for investment in projects for the conservation, restoration, and maintenance of the water basins from which the DMQ is supplied (FLACSO-PNUMA 2011). FONAG’s actions are located in the provinces of Pichincha and Napo, in nine areas: Pisque, Papallacta, Antisana, Pita, San Pedro, Pichincha – Atacazo, Mindo, Nororiente (Northeast), and Noroccidente (Northwest) (Figure 2).

FONAG divides its activities into four programs: Water Management, Vegetation Cover Recovery, Sustainable Water Conservation Areas, and Environmental Education (FONAG 2019). Concerning climate change, its initiatives are mainly related to the adaptive management of water, through the protection of conservation areas that allow the “reduction of risk in the face of climate change through the integrated management of water resources and promoting nature-based solutions when appropriate” (PACQ 2020). FONAG’s main scope of action is that of Water Source Areas (WSAs), where awareness-raising and education strategies are carried out for key actors; generation of technical, environmental, and social information; restoration of vegetation and soil cover; and conservation of wetlands, páramo, forests, and scrublands (Coronel 2019). Regarding mitigation, there is an important job made by the Vegetation Cover Recovery Program and Sustainable Water Conservation Areas, that allow the protection of relevant ecosystems for carbon capture and storage (wetlands, páramo, and forests).

FONAG’s vision is “to be recognized by Quito inhabitants and internationally as a benchmark in the conservation of water source ecosystems” (FONAG 2019) through the development of projects with a technical, social equity, and sustainability approach. These projects and programs are executed with the creation of alliances based on trust, will, and commitment, for which sustainability agreements are reached with communities and private actors, formalized, and put into practice through comprehensive action plans that include conservation and sustainability commitments.

Some of the private companies involved are the National Brewery (CN) and Tesalia CBC, with whom awareness campaigns are carried out on the origin of water as they are large users of it. Environmental education campaigns are conducted with teachers from schools located in areas of water interest that link art and education (Figure 3), involving professional artists (theater, music, puppets, etc.). In the field of environmental communication, awareness-raising tours are carried out with key actors (for example, boys and girls in the fifth year of basic education, the media, authorities, constituents of the fund, among others). Likewise, FONAG led the formation of the Environmental Education Network (REA Quito) in 2013, “a proactive network that seeks to promote and articulate environmental education in the Metropolitan District of Quito” (FONAG 2019).

In its 21 years of operation, FONAG has registered several important achievements such as: establishing a body of 23 páramo guardians that manage 19,870 acres of “own” lands bought by EPMAPS or FONAG itself; signing of 18 conservation agreements with private and community owners for 6,593 acres; restoration of 15,374.51 acres of degraded and historically overgrazed páramo; establishment of 4 monitoring sites that generate relevant information for decision-making; 46,725 participants in education and awareness-raising processes on the importance of water source ecosystems; establishment of the Agua y Páramo Scientific Station that links researchers with decision-makers and monitoring the impact of their interventions that have generated an average annual yield of 7.5% (Coronel 2019, FONAG 2019).

FONAG is led by a Technical Secretary and has a working team of 21 technicians, 23 páramo guardians, 7 educators, 3 communicators, 3 operational/logistics, and 6 administrative. Team members come from various professional areas such as hydrology, biology, ecology, geography, sociology, finance, education, and more. The páramo guardians are the core team in the surveillance and monitoring of water sources because they sustain the community work since they are women and men natives of the communities and nearby towns of these ecosystems who are connected with their environment and work directly with FONAG.

The trust structure provides FONAG with two vital features to be successful: financial resources and time (Coronel 2019). One of the challenges is to keep building synergies with its constituents and strategic allies in order to articulate efforts around water. Another critical point regarding water sources in Quito is the high consumption of drinking water, mainly in the urban areas, while the rural areas are scarce. According to EPMAPS (2015), a family from Quito uses an average of 24 thousand liters of drinking water monthly which represents an endowment of 200 liters by a person daily, approximately. And although this does not represent FONAG’s scope of action but EPMAPS’ one, it is necessary to work in a coordinated manner in awareness programs to promote co-responsibility between citizens.

Another challenge is to improve pedagogical planning and the evaluation system to transcend traditional behaviorist education and change perspectives to a constructivist environmental education according to Fernanda Olmedo (FONAG’s Environmental Education Coordinator). She also mentioned that it is necessary to strengthen the gender and ethnic approach in FONAG’s programs. Additionally, work is being done to expand the work to other water supply areas for the city, such as the Chocó Andino, where FONAG does not have a major impact at the moment.

The trust model lets FONAG have permanent income that has helped to maintain programs within the years, bringing good results. This is a model that could serve as a reference to expanding in other latitudes. As a remarkable fact, FONAG got to declare the Reserve Ponce-Paluguillo as the first Water Protection Area (APH) for the country, and South America, in 2018. This was feasible due to the joint work between FONAG, Secretaría Nacional del Agua (SENAGUA, National Water Secretariat), the contribution of the private landowner, Camilo Ponce Gangotena, and the users from Junta Administradora de Agua Potable San José del Tablón (Potable Water Administration Community Board), Junta de Riego de San José del Tablón (Irrigation Community Board) and Asociación de Pequeños Productores y Comercializadores de Hortalizas y Animales Menores el Tablón (Association from Small Vegetable Producers and Small Animals Vendors) (Ministerio del Ambiente 2018). Located in the way Pifo-Papallacta, this reserve comprises 4,260.63 acres and it is an important area for water catchment for Quito as well as a refuge for animals such as the spectacled bear, the Andean tapir, the condor, among others (Diario La Hora 2018). In this area, an Interpretation Center was built where environmental education activities are performed for diverse stakeholders.

FONAG has managed to work in a coordinated manner with the National Parks and Protected Areas (PANE), such as the Ilinizas, the Cotopaxi, the Antisana, and the Cayambe-Coca. It also manages the Water Conservation Areas: Antisana (Figure 4), Atacazo, and Alto Pita which are important in the provision of water for Quito. Ultimately, FONAG plays a key role to maintain a sustainable water cycle and water security in Quito since it has developed the power to convene different stakeholders around a common goal through long-term planning.

References

Concejo Metropolitano de Quito. 2007. Ordenanza Municipal Nº 213: Ordenanza Sustitutiva del Título V “Del Medio Ambiente” Protección de las Cuencas Hidrográficas que abastecen al Municipio del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito.

Coronel, Lorena (FONAG). 2019. Los Caminos Del Agua – FONAG: Trabajos y Aprendizajes.

Diario La Hora. «Ponce-Paluguillo, primera reserva hídrica ecuatoriana.». 03 de diciembre de 2018. https://lahora.com.ec/noticia/1102205316/ponce-paluguillo-primera-reserva-hidrica-ecuatoriana (último acceso: 30 de julio de 2021).

EPMAPS – Empresa Pública Metropolitana de Agua Potable y Saneamiento del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito. 2015. Memoria de Sostenibilidad.

FLACSO-PNUMA. 2011. Perspectivas Del Ambiente y Cambio Climático En El Medio Urbano Quito: ECCO DMQ. Programa de Las Naciones Unidas Para El Medio Ambiente PNUMA. www.flacso.org.ec

FONAG. Fondo para la Protección del Agua, Conócenos, Qué hacemos. 2019. http://www.fonag.org.ec/web/conocenos-2/ (último acceso: 15 de julio de 2021).

FONAG. Fondo para la Protección del Agua, Programas, Educación Ambiental. 2019. http://www.fonag.org.ec/web/programas/educacion-ambiental/ (último acceso: 20 de julio de 2021).

Ministerio del Ambiente. Ponce-Paluguillo es declarada la primer Área de Protección Hídrica del Ecuador y de la región. 03 de diciembre de 2018. https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/ponce-paluguillo-es-declarada-la-primer-area-de-proteccion-hidrica-del-ecuador-y-de-la-region/ (último acceso: 25 de julio de 2021).

Secretaría de Ambiente del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito y C40. 2020. Plan de Acción de Cambio Climático de Quito 2020. Primera edición. Quito, Ecuador: Municipio del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito.

For this entry, an in-depth interview was conducted with the Coordinator of the Environmental Education Program of FONAG, Fernanda Olmedo. Also, documentary research was done. Finally, information was collected from FONAG’s webpage: http://www.fonag.org.ec/web/