Occupy Goes Global!

Paraíba

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Paraíba

Scroll for more

In 2020 OCC! expanded its scope and encouraged students to explore local initiatives in their city, resulting in entries from various locations. Here below you find the entries from Paraíba

Scroll for more

Bruno Azevedo Prado

Where is this grassroots initiative implemented? Who are the promoters? Who are the beneficiaries?

The Borborema Territory is located in the Brazilian semiarid region, particularly in the Agreste region of the state of Paraíba. The Brazilian semiarid is one of the largest semiarid regions on the planet. It covers a geographical area of 970,000 Km2, concentrated in states of Northeast Brazil, and is home to a population of 22.5 million inhabitants (12% of the national population) with 44% living in rural areas, making it the least urbanized region of the country (Petersen, 2015). Polo da Borborema (Borborema Pole) was established in 1996 in partnership with NGO AS-PTA. It is presented as a family farming organization that gathers 14 rural workers’ unions, about 150 community associations, a regional association of ecological farmers, and informal groups of women and young people. Organizations affiliated to Polo da Borborema accounts to approximately 6,000 families from 15 municipalities in the hinterland of Paraíba. Since it was established, it has developed actions aimed at the economic, social, and political strengthening of family farming in the region. To this end, it implements a program of technical training and dissemination of agroecological innovations based on the principles of living with the semi-arid and agroecology, and works to influence public policies, particularly those aimed at promoting food and nutrition security and income generation for families.

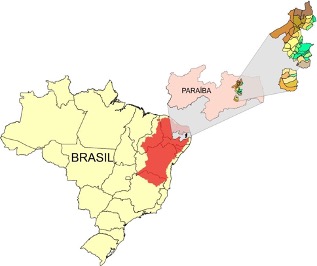

The map below depicts the 15 municipalities covered in the area where Polo da Borborema implements its actions.

Source: AS-PTA

How does this initiative engage with climate?

By proposing an alternative development for agriculture in the territory, Polo da Borborema has refused a model of neo-extractivism that permeates the complex geographies of Latin America. Working as political actor engaged in environmental justice issues, Polo has, for about twenty years, engaged with another network of civil society organizations – the Brazilian Semi-arid Articulation (ASA). Together in this macro regional project, they developed the idea that farmers, social organizations, and government agencies should change the paradigm that historically mobilized rural development in the region. Instead of “combatting the drought”, a political and institutional practice based on large infrastructure projects and the maintenance of regional oligarchies’ interests, this network of civil society proposed, based on local and traditional peasant knowledge, the idea of “living with the semi-arid” [convivência com o semiárido]. The proposal of “living with the semiarid”, taken as a paradigm of development distinct from the modernization of agriculture based on “fighting the drought” in northeastern Brazil, implies the revitalization and mobilization of locally available resources that guarantee resilience to agroecosystems. It led to the formulation of public programs for the construction of one million cisterns through new institutional arrangements involving the State and civil society. This idea re-situates agroecological transition processes based on living with the semiarid as situated technical projects that offer alternatives to the logics of modernization and to the view, based on environmental and geographical determinism, of the semiarid region as “problematic”.

This proposal is well summarized by Medeiros (2022):

In recent decades, peasant networks have flourished, encouraged by the broad macro-regional movement called Convivência com o Semiárido. They are forming communities with the unique feature of not being territorially contiguous — intensive communities whose strength lies in the recovery and reinvention of agroecological practices, and in the constant exchange of experienced knowledge. Through rainwater harvesting, the recovery of water springs, the reforestation of the Caatinga, the implementation of agroforestry systems, fair forms of animal husbandry and forest extraction, the cessation of burnings and poisoning, the gathering, exchanging, protecting, and selecting native seeds, and many other molecular and pervasive actions, these collectives directly confront the hydro-agribusiness model that has been creating desertification for centuries, and whose non-fruits are there for all to see: in the history of the genocides called droughts, in the wandering lives of landless Indigenous peoples and peasants, in the increasingly accentuated heat, in the increasingly sporadic rains, in the increasingly sandy and stony ground, and in the consequent difficulty for pioneer plants to recover the soil and the microclimate.

The idea of coexisting with the semiarid is, thus, a situated technical project, based on local knowledge and scaled-up in intensive communities across the region. It tells possibilities to occupy climate change narratives with stories that go against external solutions imposed by mainstream development.

What are the main objectives? What are the main values?

As the Declaration of the International Forum of Agroecology (2015) states

Agroecology is a way of life and the language of Nature, that we learn as her children. It is not a mere set of technologies or production practices. It cannot be implemented the same way in all territories. Rather it is based on principles that, while they may be similar across the diversity of our territories, can and are practiced in many different ways, with each sector contributing their own colors of their local reality and culture, while always respecting Mother Earth and our common, shared values.

This refers to core values that Polo da Borborema holds in its understanding of how agroecology is to be implemented in its actions. It also takes into account the idea that agroecology is understood as a science, as a practice and as a social movement. The establishment of the Pole has been the result of a renewal of the rural workers’ unionism in the territory and it has the political perspective of acting collectively, in networks and on a regional scale, to overcome the isolation represented by sole action restricted to the municipal level.

This strategy of acting collectively as a network, on a regional scale, accounts for an accumulation of learning and experience for the union movement and to participate and influence a territorial approach.

What is the timeline?

Polo da Borborema was created in 1996 and formally established as an organization in 2004, as a result of the aforementioned renewal of rural workers’ unions in the territory. As Petersen (2015) argues, the movement for a new unionism has been the result of decades of unions’ strategy focused on the national level with a generic agenda. The change of focus was largely stimulated, in the early 1990s, by a partnership with AS-PTA, a non-governmental organization promoting patterns of sustainable rural development and the strengthening of family farming in Brazil based on agroecology.

Who are the actors involved?

Taking agroecological values seriously means being able to put farmers’ knowledge at the center and providing opportunities for their interchange. This has also implications for agronomical science, which can – and should – learn from their methods of cultivation and ingenious systems of water management under challenging ecological conditions (even if the dialogue of knowledges is not always symmetrical, not to mention the existing conflicts and power asymmetries). The protagonists of this movement, then, are the farmers-experimenters, as the peasants call themselves in this network also involving NGOs and civil society organizations. Exchange knowledge activities stimulated by Polo da Borborema enhance not only technical, organizational, and political capacities, but also the identity of farmer-experimenters.

The agroecological movement in the territory also has an important focus on women and youth. Women in general face strong obstacles to participating in the management of production systems and income access. Despite successes in developing several agroecological innovations, a patriarchal culture has remained dominant both within the family and in organizations. The inequality between men and women has been a barrier for the full implementation of agroecology across the region, although a women’s movement for autonomy has been growing stronger over the last 15 years. This movement carries out regional demonstrations annually, known as the Marches for the Women’s Lives and for Agroecology.

How would it be potentially replicable in other settings?

As with many environmental initiatives, the experience of the Polo da Borborema responds to local cultural influences and demands that are unique in the territory. But the experience of the ‘living with semi-arid’ and its macro regional scale accounts for how it can reach different areas. Above all, any replication would have to take into account the diversity of the territories, and the principle of exchange of knowledge is an important factor which enhances the possibility of replication.

Is this initiative conducive to broader changes? If yes, which?

Some results have been documented and account for transformations in the enhancement of water management, with impacts on national policies such as the One Million Cisterns Program and the One Land Two Waters Program, with the construction of decentralized infrastructure to capture, store and transport water. In terms of access to market, more than 210 farmer families are regularly marketing ecological food at eight municipal fairs, while 176 families have supplied schools and nurseries with ecological food via public policies such as the National School Feeding Program (PNAE) and the Food Acquisition Program (PAA). The Pole has also established a regional network comprising 60 community seed banks and directly reaching 1,500 families has been organized that provides advocacy for the government policy for seed distribution and the Food Acquisition Program. Political crises and the rise of a national right-wing government over the last years have led, though, to the dismantling of many public programs addressing agroecology. This has led to direct impacts for family farmers and civil society agroecological networks. But they remain strong in their commitment to accountability, a rights-based State and citizenship – for it is only under such circumstances that agroecology and democratization of food systems can achieve better results.

References:

Declaration Of The International Forum For Agroecology, Nyéléni, Mali: 27 February 2015. Development 58, 163–168 (2015). Https://Doi.Org/10.1057/S41301-016-0014-4

Haraway, Donna. Staying With The Trouble: Making Kin In The Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Medeiros, R. Seridoão (Part I) Or There And Back Again, Or A Terran Testimony. In Https://Aperfectstorm.Net/Seridoao-Part-I/

Petersen, P. “Hidden Treasures: Reconnecting Culture And Nature In Rural Development Dynamics” In Constructing A New Framework For Rural Development. Published Online: 09 Mar 2015; 157-194. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1108/S1057-192220150000022006

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. Et Al. “A Safe Operating Space For Humanity.” Nature 461, 472–475 (2009). Https://Doi.Org/10.1038/461472a