Cecilia Cicchetti

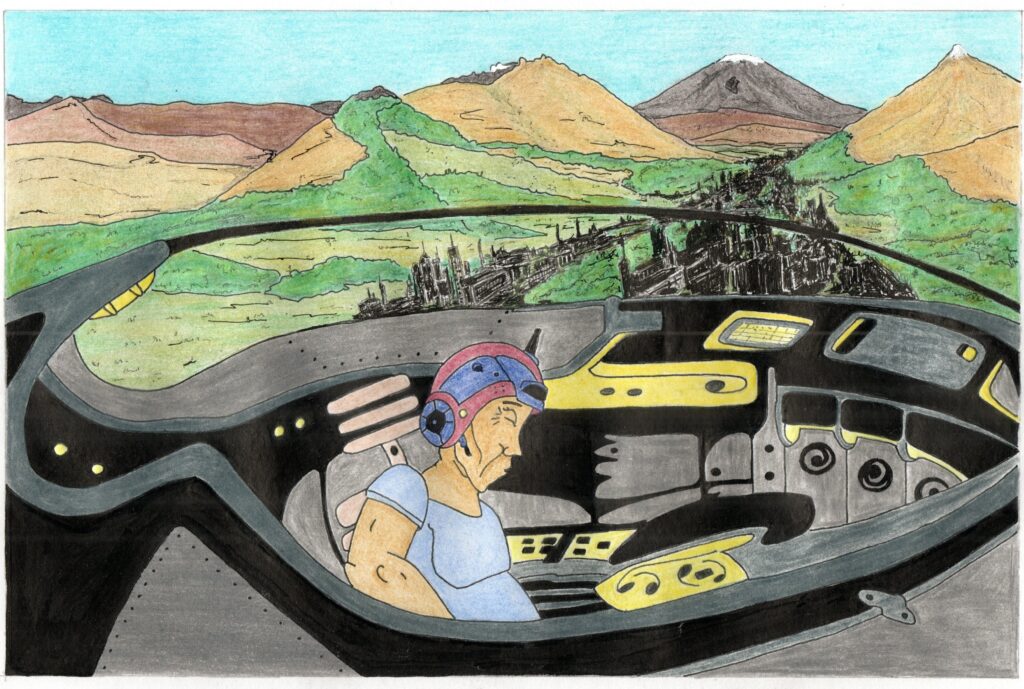

“You know, it’s been ages since people have lived so peacefully.”

“Ma, when you say things like that, I think you’re getting closer and closer to collapsing.”

It was not the first time I had questioned my mother’s sanity, and she, on this occasion too, answered as she always did. The wrinkles at the edges of her mouth became deeper, her lips opened to reveal a smile with a few less teeth, and then followed her unmistakable hoarse, dark laugh.

“Why, do you really think that you’re not insane?”

The question was more than legitimate, but after all, in those years the very concept of sanity had become almost a joke, an ancient legacy of a society that had been dead for over a century. Mum used to talk about when in her mother’s time, the grandmother I never knew, there were people who studied for over ten years for this. Her words depicted an extremely peculiar ritual: people sitting or lying on very comfortable chairs, who for an hour talked to these “mind professionals” about their problems, their darkness. And these professionals, with just a few simple words, were able to banish the darkness, if only temporarily, giving incredible relief to patients who got up from their chairs feeling much lighter. Each time, to myself, I thought about how now a little darkness and a little extra weight wouldn’t hurt anyone.

Every day the sun beat down so hard on our long, thin bodies that at night, the only respite from this exposure, it was impossible to sleep close to each other because of the heat that our dry skin emanated for hours on end. The air conditioners had become completely useless because we had now incorporated the heat into every cell of our bodies. Given the overabundance of electricity produced daily, some of us kept them on all day long, but it was a matter of habit rather than the search for a solution: air can do nothing when there is no water. My mother, looking at me and my sisters, used to sigh how we, in her mother’s time, would be chosen by the best fashion brands to wear sumptuous dresses and parade on long catwalks, covered by the flashes of the photographers and the comments of the rich guests sitting in the front row. The world before my mother must have been truly strange, full of futile practices deified for the complacency of a few, and the vain hopes of many.

“Bastards, it’s their fault if we have to live like this. If only I could go back in time…”

“Let’s hear it, what would you do?”

“Giulié, I would kill them all! One by one, these cowards! First, they ruined our lives, then they went up there. I hope they all died immediately! No, I hope they suffered at least as much as we suffered here!”

“Listen to you! Angela the revolutionary! I think they got your surname wrong at the registry, it can’t be Rotili, it must be Davis!”

“Laugh all you want, but you simply cannot understand. You were born like this, you have no clue about what we were, what we could have been! For me it’s way worse, it’s like they let me eat just a little piece of fat from a big, juicy steak, only to have it taken off in front of me a few moments later! In the meanwhile, they were laughing at me, at us: can you believe it? They didn’t care about us, they had it all… you simply cannot understand, let’s not talk about it anymore”.

Indeed, I didn’t even know what a steak was.

MORNING

Every morning began the same way. The alarm clock was given by the first, fiery ray of sunlight coming through the windows, so hot that it could interrupt even the deepest of sleeps. Our flat in Porta Furba street, like every other buildings, had not been designed to shield that level of intensity of solar activity: the concrete walls became scorching hot, and you could barely walk on the floor, despite the fact that our father had covered everything with infrared-repellent ceramic. All of that work for nothing, since the engineering efforts of the previous century had failed to predict and prevent the hellish consequences of such a thinning of the ozone layer. The entire Roman population, by then almost three hundred thousand people, therefore poured into the streets at first light to reach the places of co-operation, or to continue resting in the cool areas. On my way to the cooperative, I encountered many of these cool areas, large areas of grass planted in the middle of the pavements covered by a technological ceiling, made of a layer of solar panels and a layer of micro-fiber cloth, that managed to shield the sun’s heat providing temporary relief for those who lay underneath. Usually, these areas were used during the lunch break, when we would all get away from the cooperatives to get together and eat what little we had.

Being in my twenties meant I still had the physical strength and mental ability for farm work, which is why the RSE (Roma South Est) assembly had assigned me to the Caffarella Agricultural Cooperative. Every morning, therefore, I would cycle the few kilometers separating my house from the fields, making sure not to ride on the few remaining roads that were still paved and therefore impractical because of the heat: I would pedal along Arco di Travertino street, passing under the old railway and the even older aqueduct, then right along Appia road until I turned left onto Peluso street, a steep descent that led to Shiva square. This was where the entrance to the agricultural park was, where an old marble plaque read ‘Tacchi Venturi square’, a name replaced following the directives of the SALP (Social Agreement of the Living Population) of 2185, section IX (Urban Planning) article 93 (Continuous memory, continuous struggle):

Article 93 – Continuous remembrance, continuous struggle

Every street, alley and square, especially if previously named in honor of useless and/or colonialist and/or ecocriminal and/or fascist and/or generally harmful men, must be re-nominated to allow the continuous and collective renewal of the memory of the struggle for freedom of the living world.

To the left of Shiva square was the ‘S. Cansiz’ Youth School, attended by all the girls and boys of the RSE assembly from 2 to 19 years of age; therefore, every morning, my sister Anna would sit on the roof rack of my bicycle and beg me to give her a lift so she could get to her first lesson on time. That morning she was particularly grumpy, she had the misfortune of suffering the heat much more than we did, and so she got very little rest at night.

“What’s up with you Ninnì?”

“Giù, what do you think? I’m sleepy and I don’t wanna go to school. I want to go to the cooperative with you!”

“Don’t worry, your time will come, don’t waste these last four years of school or you’ll regret it. What lessons do you have today?”

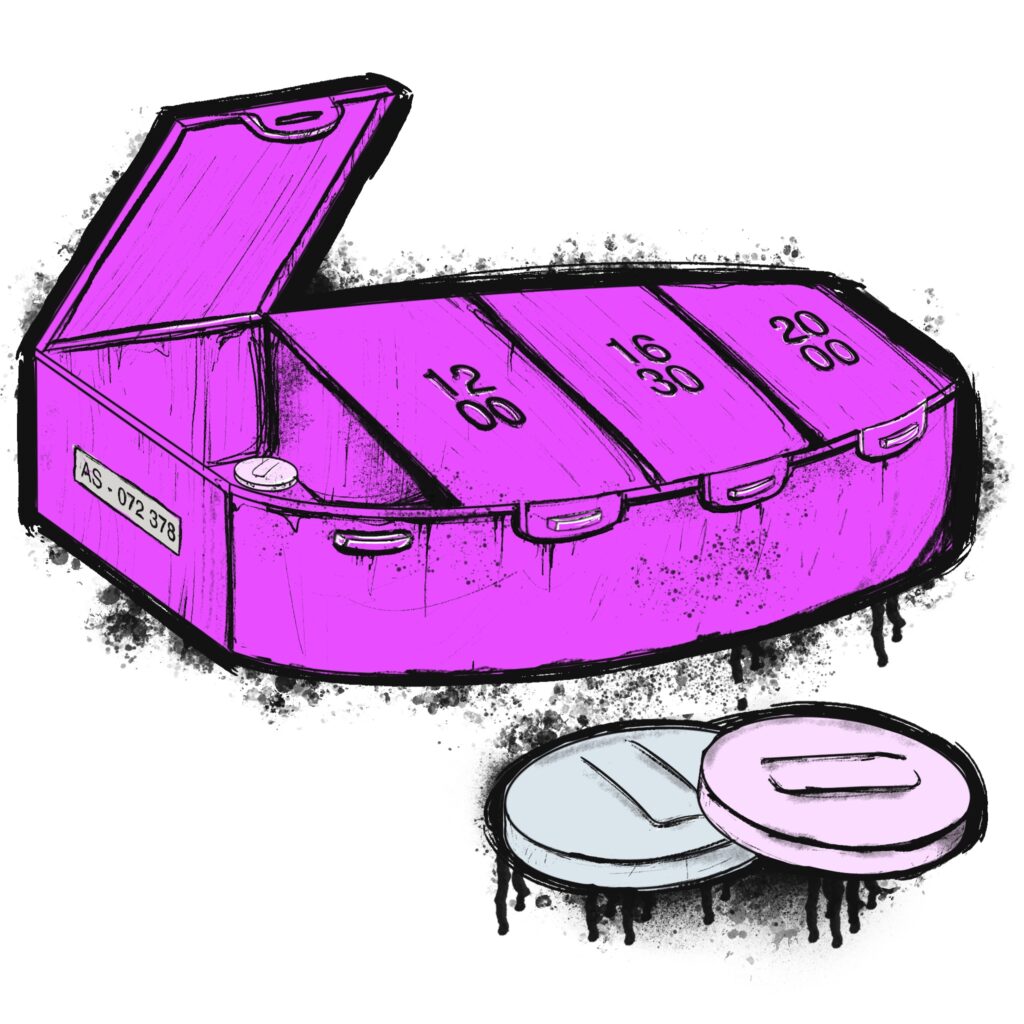

“It’s always the same… Political ecology, First aid, Collective care, Math and Medical research. I really cannot understand a single thing about Medical research, I’m always behind and whenever the teacher asks me something I don’t know what to say… what a drag”

“I feel you, I didn’t understand a thing either, but you don’t have to worry. After the graduation you are going to do whatever you want and like the most, that’s why I cooperate in the farm and, if you like it too, I’m sure that sooner than later we’ll be together in the cooperative. How cool would it be?”

She ended the conversation with a partially satisfied grunt, only because she knew that having been there, I understood her well: same classes, same professors, same vegetable garden grown for snacks. Political ecology was perhaps my favorite subject, I would listen to the professor talk for hours and hours about the extraordinary minds of some of our ancestors, while in Medical Research, just like my sister, I was really bad. However, no one had ever made me weigh that up, either in my school days or afterwards: after all, we were taught that every cooperative is of equal value when it aspires to the good of the community, a principle also written into the SALP (Section I – General Principles – Article 4 – Cooperatives and Communities).

I was especially proud of my cooperative that day, because in addition to expanding the bean, spinach and potato plantations, we had finally managed to restore the functioning of forty condensers that had been out of use for almost two years. These machines used to collect the moisture that was deposited during the night on the turf of the agricultural park, and then condense it by transforming it into drinkable and, above all, fresh water. In addition to restoring them, my comrades and I had found a way to boost the capacities of each individual condenser, which is why that morning we were all so full with excitement and anxiety: according to our calculations, if the condensers really did start working again, the availability of water per capita would return to pre-impact levels. This would have meant pure water for everyone to drink (one liter per day!) and enough fresh wastewater to ensure a daily shower for every fourth person.

“Marta, if this thing works, there’ll be a street named after us!”

“You bet Giulia! Can you believe it? Two shower per week… we’ll stink a lot less! What a dream”

“It really is a dream come true. I also think that we’ll be less hot, am I right? We’re finally going to be able to hug, even at night!”

“Giù, you’re unbelievable! We’re making Rome’s history and you’re thinking about hugging your girlfriend, unbelievable!”

“Shut up, you’re only upset because no one wants to hug you, not even your mother!”

“You know I love you but fuck you Giulia! Let’s not waste any time, we were waiting for you, milady! If it pleases you, give us the signal and we’ll coordinate for the ignition.”

This playful banter was the usual, but today wasn’t a usual day. A smile, like my mother’s but with more teeth, made its way onto my face. “Not yet,” I thought to myself, “we haven’t finished yet, no emotions, Giulia, you must concentrate”. I recomposed myself and walked to the blackboard to double-check the calculations: it was all right, everything was correct, we could proceed. Each one of us had an earpiece that allowed us to communicate at a distance, so when I shouted “Command CP23 executed” they all, at the same time, lowered the same lever on each condenser.

First the sound of one fan. Then the noise of the other thirty-nine fans joined the first one. With a trembling hand I clicked on the tank symbol on the board, and after a few seconds an inscription appeared.

_%_91.0_::__شحنة__الخزان____

I translated aloud: ‘Tank charge: 0.19%’. There was a moment’s silence, followed by an uproar of incredulous and boisterous shouting. But I could no longer hear anything, neither the fans nor the words of my comrades. Instead, I felt a strange feeling that I had experienced only once before, on the occasion of my father’s death: slow and light, a few tears were streaming down my cheeks. This time, however, it was different.

This time I was happy.

AFTERNOON

Mum greeted me screaming with joy, apparently the news had already arrived. Heedless of the asphyxiating heat, she held me in a very long hug, but this time I did not try to untangle myself out of her slender but tight grip. For several seconds we breathed the same moist, warm air, both smiling, both hopeful as two little girls. As soon as the hug dissolved, I showed her what I had brought back from the cooperative: tied to the bicycle were two big tanks of water. My mother, incredulous, slowly approached those containers and, after just barely touching them, burst into her usual laughter.

“Giulié, you’re giving us back life!”

We decided to share the wastewater as well, so that we could all take showers even if with less water. The feeling of fresh water caressing my hot skin moved me again, but even more so did the thought that my two sisters would also be able to enjoy such a luxury as soon as they came back home. My mother and I wore our clean linen robes and went to the nearest cool area, where we found other people already resting stretched out on the soft, cool grass.

“Ma, I cried two times today. Two! Unbelievable…”

“My love, what do you have to cry about? Maybe this much water is harming you!”

She had this incredible ability to downplay everything, without which she would have survived neither the impact nor her husband’s death. She often told us about the impact, much less about our father, but, in any case, she managed to turn the memory of those events into tragicomic dramas.

“You know, I hadn’t showered with fresh water since 2175. Twenty-five years washing ourselves like we washed animals in my mother’s time, fucking hell…”

“Don’t worry Ma, it’s all going back the way it was.”

“I hope not! I don’t want things to go back and be like they were before the impact. It was a shitty world, everything was wrong. But we made them pay, so much that they ran off with their flying rubbish.”

“Here we go again with this story…”

“It’s not a story, it’s history! We did it, and now we must tell you so you can learn about it, remember about it, and then tell it again. This is how we managed to reach this peace, remembering what my mother and the other comrades have taught us.”

“Of course that’s the only way for you, mainly because I think that, when the revolution stroke, you were only a child.”

“Yeah well, I too took part in it: my mother used to fight while holding me to her chest!”

“That’s convenient! If that’s true, then I’m also a revolutionary.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about! It’s a miracle that you didn’t die as a kid, you were so fragile and so tiny. Your father and I were so frightened…”

As my mother continued to narrate, I closed my eyes to fully enjoy the sound of her voice and the coolness of the grass on my neck, much less hot than usual. Immediately, however, images from ten, maybe even fifteen years ago appeared in my mind, bursting in every moment of rest to snatch me from tranquility and bring me back to reality. Images of overhanging bones, dry lips, and peeling skin; my older sister’s empty eyes, my mother’s tearful ones in front of the fire rising high from the funeral pyre. I tried to push the past and the pain out of my thoughts, concentrating on the positive things which, fortunately and despite everything, were many. The condensers, the assemblies, the days spent with my mother at the Redistributor, Roberta: thinking about her always worked. At that point I would have even been able to sleep, except that my mother’s words kept ringing out loud and clear, preventing me from any kind of rest.

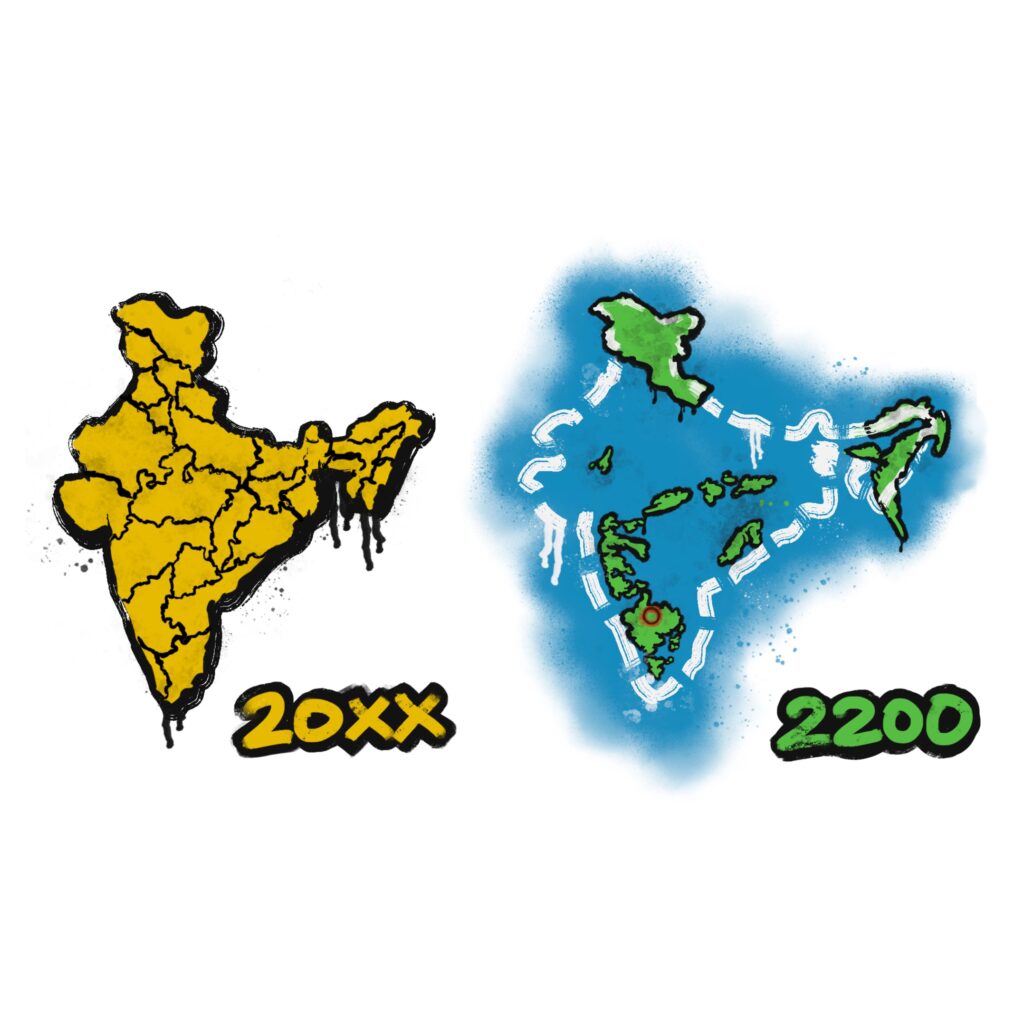

“… if you think about it, in the end everything went well. The first years were terrible, everyone was stealing even though there wasn’t anything to steal. But, I mean, just here in Rome we were fifteen million people. Fifteen million! It was inevitable, with the raising temperature the Thwaites melted, and we lost antarctica. These poor people, the only way they got to keep living in their land was if they transformed into fishes! But, I mean, in the end we managed to rebuild this world. We cried a lot and we lost almost everything, but we survived, and you know why? Because the only thing we didn’t lose was love. And here we are now, never skipping a meal again. Here you are! You became such a bright and beautiful woman, look at what you did today! My love, maybe you didn’t take part in the first revolution, but you are making one now! I’m so proud of you, and your father would have been even prouder!”

Mum paused for a second, I heard her sigh deeply. Then, perhaps moved by a pity for my tired eyes, she lay down beside me and we finally managed to fall asleep, now with a smile on our lips.

EVENING

“Thank you all for coming here tonight. I am very excited because today, as I think you have heard, is a day we will remember for a long time. Thanks to the comrades of the Caffarella agricultural cooperative, all the condensers are back in service! It is an extraordinary event and will represent an amazing improvement in our living conditions, those of our daughters and all generations to come. I would say that now, finally, we can go back to thinking about future generations, and not just ourselves. But I do not want to occupy a space that is not mine, as co-chairwoman of the RSE assembly I just wanted to share with all of you my enthusiasm and joy, but now I will turn the floor over to Giulia Rotili, co-responsible engineer of the project.”

“Thank you Ada, and thank you all for being here. I too am extremely excited, today together with the other comrades we have done something really great. I don’t want to bore you with numbers and graphs, so I will briefly summaries what it means to have capacitors up and running again. Every day each of us in the RSE assembly will have one liter of fresh, pure water and two and a half liters of fresh but impure water. We have also started the construction work on one hundred and sixty new condensers, which will be completed by 2225 and will then be distributed equally to the other roman assemblies. Once we’re done with that, we will build more for ourselves as well; we estimate that by 2230 the RSE assembly, together with all the other assemblies in Rome, will have as many as one hundred and forty functioning condensers. This is the way to ensure prosperity for all of our sisters in Rome!”

Thunderous applause followed the end of my speech, I felt my legs shaking as if the ground was about to collapse under my feet. I flashed a smile, thanked my comrades again and asked if there were any questions or requests for clarification. Giosy, well known to the assembly because of their propensity to insistently pose questions on every topic discussed, raised their hand.

“I’m sorry but, I mean… why should we care about the other assemblies? I know that we always helped each other, and ok maybe it’s the right thing, but I mean… what id we build these condensers for ourselves? Wouldn’t it be better? So that in two years we’ll reach two liters of water a day, and then we can think about the other. Am I wrong?”

An uncertain applause rose from the assembly, many comrades cast glances at each other between astonished and intrigued. Giosy’s intervention was in open violation of the first article of the SALP, going also against everything that had allowed the reconstruction of a peaceful, if painful, world. I felt the blood rush to my brain, my face turning red and my heart beating wildly against my uvula.

“Comrades, forgive me if I speak like this, but I just want to say one thing: Giosy, what the fuck are you talking about? How can you think like the ones that condemned us, the ones that for centuries taught us that we always come first and that we should never think about the others! Do you really want to go back there? To killing each other for a piece of land? For a glass of warm and shitty water? How can you say these things!”

My less-than-democratic speech was greeted by applause but also a vociferous disapproval. The background buzz grew loudly, and the assembly seemed to be about to be dissolved by the co-chairs. At that point, as always happened in such cases, Roberta raised her hand and suddenly the assembly recomposed itself, as if by magic. Roberta had this capability: over the years she had earned the esteem of her comrades in all the Roman assemblies for the incredible medical discoveries her mind had helped achieve. Her aptitude for medical research became apparent from the very first classes we attended together as desk mates. Every single one of her intuition and answer amazed me: her eyes saw aspects of reality that did not exist for me, her brain was able to process that visual information in such a rigorous way that the answer turned out much simpler than it actually was, so easy that even I could understand (at times). Thanks to her skills and manners, she had become a very respected member the community, both scientific and non-scientific, despite her young age, which is why she was able to speak without having to raise her voice.

“Dearly beloved, please pull yourself together. Both speeches were out of place, in content and manner. Giulia, you know very well that in this assembly you cannot speak like this, and you cannot express yourself in this way, however right you may be. Giosy, to repudiate the constituent principles contained in the SALP is a mistake we must not commit, simply because we cannot afford it. The only thing that has given us the chance to rebuild and preserve society, production and our very lives are those very principles: we cannot leave anyone behind, we cannot recreate the inequalities that, in the pre-impact world, condemned the masses to unhappy and inhuman lives. We are finally in the state of nature, where every living being lives on love and cooperation, and we managed to achieve it only after building a community capable of providing not only the needs of the body, but also those of the soul. We cannot, we must not turn back: selfishly, it’s not convenient for us. We will work harder to shorten the time it takes to build the new condensers, but the rules of fair redistribution will not be violated. Thank you for your attention, sisters.”

The applause overpowered the grunts of Giosy, who continued to be unconvinced by what was said but, as always, surrendered to the enthusiasm of the assembly. Dissent was heard and absorbed, and eventually enthusiasm for the prospects of a more hydrated future swept through the assembly. Chairs were moved to make room for dancing, with music filling the room and our hearts. I went to find Roberta to drag her in the middle of the dance floor, which I knew would have embarrassed her. But, despite her poise, I knew that she had never been happier.

NIGHT

All that remained of the Maestoso theater was the exterior structure since the ceiling had collapsed several years ago, and the urban regeneration committee had noted that its reconstruction would be a waste of precious resources. We had collected and recycled the rubble, some of the old halls had been turned into literary and theatrical clubs, while others had retained their old function and, when possible, open-air cinema evenings took place. Years ago, Roberta and I had found a way to access the only closed hall, which immediately became our favorite place: the seats had been taken away, all that was left was the floor, the walls and the sky above. It was our little secret, and after removing the layer of concrete and regrowing the natural vegetation, it had become the place where we met every evening. Lying on the small grassland embedded in the concrete, we enjoyed the warm embrace of the silence of that place, especially after the eventful assembly of that night. Whenever we went there, we liked to look for new constellations, an activity made almost impossible by the sky full of too many stars. We had a small notebook, placed on a shelf next to it, where we took note of the supposed new constellations to which we gave the most improbable names: ‘Gerardo’, because according to Roberta it resembled her cat, or ‘The thing we use in the lab for cellular regrowth’, again an idea of Roberta’s, who sometimes forgot the names of the most important things in her everyday life. That evening, however, we did not play, we were exhausted from the day’s work and the assembly.

“So, how did it go for you today?”

“All good come on, we’re getting closer and closer to the conclusion of the research project. It’s getting close, I can feel it: once it’s done we’ll be able to stem the danger of skin cancer as well, that would be really crazy stuff.”

“Absurd yes, you’re incredible… I still don’t understand how you can think such things!”

“Well, I don’t understand how you people managed to restore the capacitors, it’s a good thing we were properly addressed!”

“Yes, they were right on the mark at school… and then, what else are you working on?”

“Thanks to the laboratory results of the Northwest Assembly Medical Cooperative, we might be able to come up with the right formula to be able to create a sunscreen that can shield almost all solar radiation. That would be a big step forward too, but we have to wait for the answers from the comrades in Afrin to make it, I’m afraid it will take a while yet.”

As Roberta continued talking, I reached out my hand towards hers and brushed against her palm. She gasped as usual, but for a different reason: it was the first time after many attempts that the contact had not caused the rising of our temperature. Roberta stopped talking, moved her hand towards mine and placed her entire palm on mine. Holding my breath, I closed my fingers and squeezed her hand. It was bearable, infinitely pleasant. Roberta resumed speaking as if it were nothing, but in her broken voice I could hear the uniqueness of the moment, so much that when I turned my head to look at her face I noticed a tear was running down her cheek, towards her ear. I moved closer and wiped it away with a kiss, and Roberta stopped talking for good. She turned her head too, with her eyes all watery, slowly placing her lips on mine. She drew back and burst into smiling tears. I took her face in my hands and rested my forehead on hers.

“Wow! I know that this is the first time that we managed to kiss, but I didn’t know you were such a crybaby! I don’t know if I want to kiss you again after this…”

“Look who’s talking! I know that you cried two times today, I talked to your mother. By the way, what’s with the crying for the condensers but not for me? I’m utterly infuriated!”

We both laughed, then I took out a handkerchief and wiped her face. We kissed one more time, then we went back at staring the sky.

“Roberta, look! I think I found a new constellation.”

“What are you talking about, it’s impossible! Where?”

“Follow my finger, right there on the right. I never saw it before, looks like two people hugging!”

“Yeah, now I see it. How cute! How should we call it?”

After a few moments of silence Roberta suddenly turned her back to me and said “we could call it “RG”, but only if you can hug me like that”. I was extremely confused, but after a little bit I understood how and where I had to put my arms: one under her neck, the other one around her between the waist and her left arm. Incredibly hard, incredibly pleasing.

“Shall we sleep here?”

“I don’t know Robbi, tomorrow we have to go to the cooperatives and neither of us has her bicycle, it’ll be difficult…”

“All right, you’re right. Let’s not think about that now, we’ll find a way.”

After all, we had always found a way, and would always keep finding it: never alone, always together.

And, now, hugging.

Contatto – Roma 2200

Cecilia Cicchetti

“Sai, erano secoli che non si viveva così in pace”

“Mà, quando me dici ste cose penso che stai sempre più vicina al collasso”

Non era la prima volta che mettevo in dubbio la sanità mentale di mia madre, e lei, anche in quest’occasione, rispose come faceva sempre. Le rughe ai bordi della bocca diventarono più profonde, le labbra si aprirono mostrando un sorriso con qualche dente in meno, e poi seguì la sua inconfondibile risata roca e cupa.

“Perché, te pensi de esse sana?”

La domanda era più che lecita, ma in fondo in quegli anni il concetto stesso di sanità mentale era diventato quasi una barzelletta, antico retaggio di una società morta ormai da un secolo. Mamma parlava sempre di quando ai tempi di sua madre, la nonna che non ho mai conosciuto, c’erano persone che studiavano oltre dieci anni per questo. Le sue parole dipingevano un rituale estremamente peculiare: persone sedute o sdraiate su poltrone molto comode, che per un’ora parlavano a queste professioniste della mente dei loro problemi, delle loro oscurità. E queste professioniste, con poche e semplici parole, riuscivano ad allontanare l’oscurità, anche solo temporaneamente, dando sollievo incredibile alle pazienti che si alzavano dalle poltrone sentendosi molto più leggere. Ogni volta, tra me e me, pensavo a come ora un po’ di oscurità e un po’ di peso in più non avrebbero fatto male a nessuna.

Ogni giorno il sole picchiava fortissimo sui nostri corpi lunghi e magri, tanto che la notte, l’unico momento di pausa da questa esposizione, era impossibile dormire vicine a causa del caldo che la nostra pelle secca emanava per ore ed ore. I condizionatori erano diventati completamente inutili, perché il caldo ormai lo avevamo inglobato in ogni cellula del nostro corpo. Vista la sovrabbondanza di energia elettrica prodotta quotidianamente, qualcuna li teneva accesi tutto il giorno, ma era un fatto di abitudine più che la ricerca di una soluzione: l’aria non può nulla quando manca l’acqua. Mia madre, guardando me e le mie sorelle, sospirava sempre come noi, ai tempi di sua madre, saremmo state scelte dai migliori marchi di moda per indossare sontuosi vestiti e sfilare su lunghissime passerelle, ricoperte dai flash delle fotografe e dai commenti dei ricchi ospiti seduti in prima fila. Il mondo prima di mia madre doveva essere veramente strano, colmo di pratiche futili deificate per il compiacimento di pochi, e le vane speranze di moltissime.

“Bastardi, è colpa loro se viviamo sta vitaccia. Potessi tornà indietro ner tempo…”

“Che faresti, sentiamo!”

“Eh Giuliè che farei, li farei fuori a tutti! Uno per uno, sti bastardi vigliacchi! Prima c’hanno rovinato la vita, poi se ne sò annati lassù. Spero ce siano morti tutti subito! Anzi no, subito no. Spero abbiano sofferto, almeno quanto abbiamo sofferto noi dimenticate quaggiù.”

“Sentila che discorsi che fa Angela la rivoluzionaria! Se saranno sbajati all’anagrafe, te nun fai Rotili de cognome… fai Davis!”

“Se se, perculateme pure. Ma che ne volete sapè voi, che ce siete nate così. Non sapete che eravamo, che saremmo potute esse! È ancora peggio così, sai? È come se m’avessero fatto magnà solo il nervetto della bistecca più bona der mondo, e poi me l’hanno tolta da davanti l’occhi sti bastardi! E ner mentre ridevano pure, capito? Tanto loro bene stavano, che je fregava de noi… che ne sapete voi de quello che avemo passato, lasciamo perde va”.

In effetti, io non sapevo neanche cosa fosse una bistecca.

MATTINA

Ogni mattina iniziava allo stesso modo. La sveglia veniva data dal primo, infuocato raggio di sole che penetrava dalle finestre, talmente caldo da interrompere anche il più profondo dei sonni. Il nostro appartamento in via di Porta Furba, come tutti gli altri edifici, non era stato progettato per schermare quel livello di intensità di attività solare: le pareti di cemento armato diventavano roventi e a malapena si riusciva a camminare sul pavimento, nonostante nostro padre avesse rivestito ogni cosa con della ceramica infrarosso-repellente. Tutto quel lavoro per nulla, dato che gli sforzi ingegneristici del secolo precedente non erano infatti riusciti né a prevedere né a prevenire le conseguenze infernali di un tale assottigliamento dell’ozonosfera. L’intera popolazione romana, ormai quasi trecentomila persone, si riversava dunque in strada alle prime luci dell’alba per raggiungere i luoghi di cooperazione, o per continuare a riposare nelle apposite aree fresche. Lungo la strada per andare in cooperativa ne incontravo tante, erano grandi aree di manto erboso piantate in mezzo ai marciapiedi coperte da un soffitto composto da uno strato di pannelli solari e uno di panno in microfibra, in grado di schermare la calura solare assicurando un temporaneo sollievo per chi vi si sdraiava al di sotto. Di solito queste aree venivano utilizzate durante la pausa pranzo, quando tutte ci allontanavamo dalle cooperative per ritrovarci e mangiare, seppur quel poco che avevamo, insieme.

Avere vent’anni significava avere ancora la forza fisica necessaria per il lavoro agricolo, per questo l’assemblea RSE (Roma Sud Est) mi aveva assegnata alla cooperativa agricola della Caffarella. Ogni mattina, dunque, percorrevo in bicicletta i pochi chilometri che separano casa mia dai campi, assicurandomi di non passare sulle poche strade rimaste ancora asfaltate e dunque impercorribili per via del caldo: pedalavo per via dell’Arco di Travertino, passando sotto la vecchia ferrovia e l’ancor più vecchio acquedotto, poi a destra lungo via Appia fino alla svolta a sinistra su via Peluso, una ripida discesa che portava a Largo Shiva. Qui si trovava l’ingresso del parco agricolo, dove una vecchia targa di marmo recitava “Largo Tacchi Venturi”, nome sostituito in seguito alle direttive della CaSPAV (Carta Sociale delle Popolazioni Ancora Vive) del 2185, sezione IX (Urbanistica) articolo 93 (Memoria continua, lotta continua):

Articolo 93 – Memoria continua, lotta continua

Ogni strada, vicolo, largo e piazza, specialmente se precedentemente nominata in onore di uomini inutili e/o colonialisti e/o ecocriminali e/o fascisti e/o generalmente dannosi, deve essere ri-nominata per permettere il rinnovamento continuo e collettivo della memoria della lotta per la libertà del mondo vivente.

A sinistra di largo Shiva c’era la Scuola Giovanile Omnicomprensiva “S. Cansiz”, frequentata da tutte le ragazze e i ragazzi dell’assemblea RSE dai 2 ai 19 anni di età; per questo, ogni mattina, mia sorella Anna si sedeva sul portapacchi della mia bicicletta e mi pregava di darle un passaggio per poter arrivare in orario alla prima lezione. Quella mattina era particolarmente scontrosa, aveva la sfortuna di soffrire molto più di noi il caldo e quindi di notte riposava molto poco.

“Ninnì, che c’hai?”

“Giù, ma che vuoi che c’ho, ho sonno e non mi va di andare a scuola. Voglio venì a cooperà co te!”

“Tranquilla c’avrai tempo, sti quattro anni di scuola che te restano non li devi sprecà, capito? Che lezioni c’hai oggi?”

“Mah, il solito… Ecologia politica, Primo soccorso, Cura collettiva, Matematica e Ricerca medica. Solo che de ricerca non ce capisco niente, sto sempre indietro e quando la prof mi chiede qualcosa non so mai che dire… che palle”

“Eh lo so, pure io non riuscivo a starci dietro, ma non fa niente, non te devi preoccupà. Dopo la scuola farai quello che ti piace di più, per questo a me m’hanno messa ai campi, se piace anche a te vedrai che verrai con me, pensa che tajo!”

Mi rispose chiudendo la conversazione con un grugnito parzialmente soddisfatto, solo perché sapeva che, essendoci passata, la capivo bene: stesse lezioni, stesse professoresse, stesso orto coltivato per le merende. Ecologia politica era forse la mia materia preferita, avrei ascoltato la professoressa parlare per ore ed ore delle straordinarie menti delle nostre antenate, mentre in Ricerca medica, esattamente come mia sorella, ero veramente scarsa. Nessuno però me lo aveva fatto mai pesare, né ai tempi della scuola né dopo: dopotutto ci hanno insegnato che ogni cooperativa ha lo stesso valore quando fa il bene della comunità, principio scritto anche nella CaSPAV (Sezione I – Principi Generali – articolo 4 – Cooperative e comunità).

Quel giorno ero particolarmente orgogliosa della mia cooperativa perché, oltre ad aver ampliato le piantagioni di fagioli, spinaci e patate, eravamo finalmente riuscite a ripristinare il funzionamento di quaranta condensatori fuori uso ormai da quasi due anni. Questi macchinari permettevano di raccogliere l’umidità che di notte si depositava sui manti erbosi del parco agricolo, per poi condensarla trasformandola in acqua potabile e, soprattutto, fresca. Oltre a ripristinarli, io e le mie compagne avevamo trovato il modo di potenziare le capacità di ogni singolo condensatore, e per questo quella mattina in cooperativa c’era un’aria diversa, si respirava l’ansiosa ed eccitata attesa della speranza: secondo i nostri calcoli, se i condensatori avessero veramente ricominciato a funzionare, la disponibilità di acqua pro capite sarebbe tornata ai livelli pre-impact. Ciò avrebbe significato acqua pura da bere per tutte (un litro al giorno!) e acqua di scarto a sufficienza da garantire una doccia giornaliera per una persona ogni quattro.

“Aò Marta, se sta robba funziona poi ce devono intitolà na strada pure a noi eh!”

“Avoja Giulié! Ma ve rendete conto? Due docce a settimana… pensa a quanto puzzeremo de meno!”

“Che sogno! Ma poi c’avremo anche meno caldo, no? Finalmente se potemo abbraccià quando dormimo de notte!”

“A Giulié, sei incredibile! Noi qua stamo a fa la storia de Roma e te pensi a abbraccià la ragazza tua, nce se crede!”

“Aò lasciame perde, stai solo a rosicà perché a te ‘nte s’abbraccerebbe manco tu madre”

“… ‘cci tua, lasciamo perde va! Comunque stavamo aspettando te signorinella, quando vuoi dacce il segnale e ci coordiniamo per l’accensione”

Un sorriso, come quello di mia madre ma con più denti, si fece largo sul mio viso. “Ancora no” pensai tra me e me, “ancora non abbiamo finito, niente emozioni Giulia devi concentrarti”. Mi ricomposi e camminai verso la lavagna per ricontrollare i calcoli: era tutto a posto, tutto corretto, potevamo procedere. Ognuna di noi aveva un auricolare che permetteva di comunicare a distanza, per questo quando urlai “Comando CP23 eseguito” tutte, contemporaneamente, abbassarono la stessa leva posta su ogni condensatore.

Prima il rumore di una ventola. Poi di altre trentanove ventole che si univano alla prima. Con la mano tremante cliccai sul simbolo del serbatoio sulla lavagna, e dopo qualche secondo apparve una scritta.

_%_91.0_::__شحنة__الخزان____

Tradussi ad alta voce: “Carica serbatoio: 0.19%”. Ci fu un momento di silenzio, seguito da un frastuono di urla incredule e sguaiate. Ma io non sentivo più nulla, né le ventole, né le parole delle mie compagne. Sentivo solo una strana sensazione, provata soltanto una volta prima di allora in occasione della morte di mio padre: lente e leggere, alcune lacrime scendevano lungo le mie guance. Solo che stavolta era diverso.

Stavolta ero felice.

POMERIGGIO

Mamma mi accolse urlando di gioia, evidentemente la notizia era già arrivata. Incurante del caldo asfissiante mi strinse in un abbraccio lunghissimo, e io, al contrario del solito, non cercai di svincolarmi dalla sua presa esile ma serrata. Per diversi secondi respirammo la stessa aria umida e calda, entrambe sorridenti, entrambe speranzose come due bambine. Appena sciolto l’abbraccio le mostrai ciò che avevo riportato dalla cooperativa: legate alla bicicletta c’erano due taniche d’acqua. Mia madre, incredula, si avvicinò lentamente a quei recipienti e, dopo averli sfiorati appena, esplose nella sua solita risata.

“La vita Giulié, ce state a ridà la vita”

Decidemmo di dividere anche l’acqua di scarto, così da poter permettere a tutte di fare la doccia anche se con meno acqua. La sensazione dell’acqua fresca che accarezzava la mia pelle bollente mi commosse di nuovo, ma ancor di più mi emozionò il pensiero che anche le mie due sorelle avrebbero potuto godere di tale lusso non appena tornate a casa. Io e mia madre indossammo le vesti di lino pulite e ci recammo all’area fresca più vicina, dove trovammo altre persone che già riposavano stese sull’erba morbida e fresca.

“Mà, lo sai che oggi ho pianto due volte? Due! Ma pensa te…”

“Fija mia e che c’hai da piagne? N’è che tutta st’acqua te farà male?”

Aveva quest’incredibile capacità di sdrammatizzare tutto, senza la quale non sarebbe sopravvissuta né all’impact né alla morte di suo marito. A noi raccontava spesso dell’impact, molto meno di nostro padre, e, in ogni caso, riusciva a trasformare il ricordo quegli eventi in drammi tragicomici.

“Giuliè, non me facevo na doccia co dell’acqua fresca dar 2175 lo sai? Venticinque anni a lavasse come ai tempi de mi madre lavavano le bestie, che finaccia…”

“Vabbè Mà nte preoccupà, mo tornerà tutto come prima, no?”

“Ma chi ce vole tornà a prima dell’impacte! Te l’ho sempre detto, era un mondo demmerda, era tutto sbajato. Je l’avemo fatta vedè però, adavede come se ne so scappati su quei cosi volanti, sti bastardi”

“Aridaje co sta storia…”

“Non è na storia, è la storia! Se nun ve la racconto a che è servito fallo? Dovete imparà, dovete ricordà e dovete raccontà. Come pensi che l’abbiamo raggiunta sta pace? Ricordando quello che c’hanno insegnato mi madre e tutte l’artre compagne.”

“Anche perché a me me pare che te manco camminavi quando hanno fatto la rivoluzione, o sbajo?”

“Beh l’ho fatta pure io alla fine, se pensi che mi madre combatteva co me in petto”

“E certo, così so boni tutti però… allora posso dì che pure io ho fatto la rivoluzione”

“Ma lassa perde, te già è tanto che nsei morta da regazzina. Eri no scricciolo, respiravi pianissimo, non te se vedeva e non te se sentiva. Io e tuo padre c’avevamo tanta de quella paura…”

Mentre mia madre continuava a raccontare, chiusi gli occhi per godere a pieno del suono della sua voce e del fresco dell’erba sul collo meno rovente del solito. Subito però mi apparvero in mente le immagini di dieci, forse anche quindici anni fa, che irrompevano in ogni momento di riposo per strapparmi alla tranquillità e riportarmi alla realtà. Immagini di ossa troppo sporgenti, di labbra secche e pelle squamata; gli occhi vuoti di mia sorella maggiore, quelli pieni di lacrime di mia madre davanti al fuoco che si levava altissimo dalla pira funebre. Cercai di allontanare il passato e il dolore dal pensiero, concentrandomi sulle cose positive che, per fortuna e nonostante tutto, erano molte. I condensatori, le assemblee, le giornate passate con mia madre al Redistributore, Roberta: pensare a lei funzionava sempre. A quel punto sarei anche riuscita a dormire, se non fosse che le parole di mia madre continuavano a risuonare forti e chiare, impedendomi qualsiasi tipo di riposo.

“… però alla fine è annata bene no? C’è voluto un po’ e i primi anni so stati veramente tosti: tutti che rubbavano, anche se nc’era niente più da rubbasse. Ma immaggina che qui a Roma eravamo più de quindici milioni. Quindici milioni! Pe forza, co cinque gradi in più s’era sciolto il ghiacciaio gigante, il Thwaites, pensa te ancora me ricordo quer nome strano… è lì che se semo giocati l’Antartide, e poi per forza che tutta sta gente è venuta a Roma, pe potè restà a casa loro dovevano trasfommasse in pesci! Però alla fine ci siamo riuscite, l’abbiamo ricostruito sto mondo. Avemo pianto tanto, e perso quasi tutto, però je l’avemo fatta e sai perché? Perché l’unica cosa che non avemo mai perso è l’amore. E anfatti guarda te adesso, da quant’è che non digiuniamo eh? Guarda tu quanto sei diventata bella e brava, guarda che hai fatto oggi! Amore mio, non avrai fatto la rivoluzione da regazzina come me, ma te la stai a fa adesso! So così fiera di te, e papà lo sarebbe ancora de più.”

Mamma si interruppe un secondo, la sentii sospirare profondamente. Poi, forse mossa da un moto di pietà nei miei confronti dei miei occhi stanchi, si stese accanto a me e finalmente riuscimmo ad addormentarci, ora con il sorriso sulle labbra.

SERA

“Grazie per essere venute tutte qui stasera. Sono molto emozionata perché oggi, come penso abbiate saputo, è un giorno che ricorderemo a lungo. Grazie alle compagne della cooperativa agricola della Caffarella tutti i condensatori sono tornati in funzione! È un evento straordinario e rappresenterà un netto miglioramento delle nostre condizioni di vita, di quelle delle nostre figlie e di tutte le generazioni a venire. Direi che ora, finalmente, possiamo tornare a pensare alle generazioni future, e non solo a noi stesse. Ma non voglio occupare uno spazio che non mi compete, in quanto co-presidenta dell’assemblea RSE volevo solo condividere con tutte voi il io entusiasmo e la mia gioia, ora però trasferisco la parola a Giulia Rotili, ingegnera co-responsabile del progetto”.

“Grazie Ada, grazie a tutte e tutti per essere qui. Anche io sono estremamente emozionata, oggi insieme alle compagne abbiamo fatto un qualcosa di veramente grande. Non voglio tediarvi con numeri e grafici, quindi vi riassumerò in breve cosa significa avere di nuovo in funzione i condensatori. Ogni giorno ognuna di noi dell’assemblea RSE avrà a disposizione un litro di acqua fresca e pura e due litri e mezzo di acqua fresca ma impura. Abbiamo inoltre avviato i cantieri per la costruzione di altri centosessanta condensatori, che saranno ultimati entro il 2225 e che poi verranno distribuiti equamente alle altre assemblee. Una volta fatto ciò ne costruiremo altri anche per noi, stimiamo che entro il 2230 l’assemblea RSE, insieme a tutte le altre assemblee romane, avrà ben centoquaranta condensatori funzionanti. Solo così garantiremo la prosperità per tutte le nostre sorelle di Roma!”

Applausi scroscianti seguirono la fine del mio discorso, sentivo le gambe tremare come se mi stesse per crollare il terreno sotto ai piedi. Accennai un sorriso, ringraziai ancora le compagne e chiesi se ci fossero domande o richieste di chiarimenti. Alzò la mano Giosy, nota come “Er polemica” data la sua propensione a porre insistentemente questioni su ogni argomento trattato in assemblea.

“Scusateme tanto, però vojo dì… a noi che ce dovrebbe fregà dell’artre assemblee? Va bene che se semo sempre aiutati, e vabbè che pare che è giusto così, però insomma… se sti condensatori li costruissimo prima pe noi n’sarebbe mejo? Così intanto no’artre magari tra du anni arivamo a beve du litri d’acqua, e poi, co la pancia più piena, pensamo pure all’altre. O me sto a sbajà?”

Un applauso incerto si levò dall’assemblea, molte compagne si lanciarono sguardi tra lo sbalordito e l’incuriosito. L’intervento di Giosy era in aperta violazione con il primo articolo della CaSPAV, ma in generale andava contro tutto ciò che aveva permesso la ricostruzione di un mondo pacifico, seppur dolente. Sentii il sangue salirmi al cervello, la faccia diventare rossa e il cuore battere fortissimo contro l’ugola.

“Compagne, scusate se prendo la parola così, ma mi preme sottolineare questa cosa: a Giosy, ma che cazzo stai a dì? Ma come te viene de raggionà come quelli che c’hanno condannato a questa vita, quelli che per secoli c’hanno detto che prima venimo noi e poi l’artri, ed ecco il risultato. Davero vogliamo tornà a esse così? A ammazzasse pe n’pezzo de terra, pe n’bicchiere d’acqua zozza e calla? Ma come se fa, come se fa!”

Il mio intervento non proprio democratico venne accolto da applausi ma anche da un vociare di disapprovazione. Il brusio di sottofondo crebbe fino ad occupare ogni spazio acustico, e l’assemblea sembrava essere in procinto di venir sciolta dalle co-presidenti. A quel punto, come sempre succedeva in questi casi, alzò la mano Roberta e, improvvisamente, l’assemblea si ricompose, come per magia. Roberta faceva questo effetto, negli anni si era guadagnata la stima delle compagne di tutte le assemblee romane per le incredibili scoperte mediche che la sua mente aveva contribuito a raggiungere. La sua predisposizione per la ricerca medica si palesò fin dalle prime lezioni che frequentavamo insieme, noi compagne di banco fin dai primi anni di scuola. Ogni suo intervento, ogni sua risposta mi meravigliava: i suoi occhi vedevano aspetti del reale per me inesistenti, il suo cervello riusciva ad elaborare queste informazioni visive in un modo talmente rigoroso che la risposta risultava molto più semplice di quanto in realtà non fosse. Grazie alle sue abilità e ai suoi modi era diventata un punto di riferimento per la comunità, scientifica e non, nonostante la sua giovane età: per questo riuscì a prendere parola senza dover alzare la voce.

“Care e cari, per favore ricomponiamoci. Entrambi gli interventi sono stati fuori luogo, per contenuto e per modo. Giulia, sai bene che in quest’assemblea non si può prendere parola così e non ci si può esprimere in questo modo, per quanto tu possa aver ragione. Giosy, rinnegare i principi costituenti contenuti nella CaSPAV è un errore che non dobbiamo commettere, anzi, che non possiamo permetterci di commettere. L’unica cosa che ci ha dato la possibilità di ricostruire e preservare la società, la produzione e le nostre stesse vite sono proprio quei principi: non possiamo lasciare nessuna indietro, non possiamo ricreare le disuguaglianze che, nel mondo pre-impact, condannavano le masse a vite infelici e disumane. Ci troviamo finalmente nello stato di natura, dove ogni essere vivente vive di amore e collaborazione, e l’abbiamo raggiunto solo dopo aver costruito una collettività in grado di sopperire non solo alle necessità del corpo, ma anche a quelle dell’anima. Non possiamo, non dobbiamo tornare indietro: egoisticamente, non ci converrebbe. Lavoreremo più intensamente per abbreviare i tempi di costruzione e messa in uso dei condensatori, ma le regole di redistribuzione equa non verranno violate. Grazie per l’attenzione, sorelle”.

Gli applausi sovrastarono i grugniti di Giosy, che continuava a non essere convint3 di quanto detto ma che, come ogni volta, si arrese all’entusiasmo dell’assemblea. Il dissenso era stato ascoltato e riassorbito, e alla fine l’entusiasmo per le prospettive di un futuro più idratato tornò a travolgere l’assemblea. Le sedie vennero spostate per far spazio alle danze, con la musica che riempiva la stanza e i nostri cuori. Andai a cercare Roberta per trascinarla al centro della sala, cosa che sapevo l’avrebbe messa in imbarazzo. Ma, nonostante il suo contegno, sapevo che non era mai stata così felice.

NOTTE

Del cinema Maestoso non rimaneva altro che la struttura esterna, il soffitto era crollato diversi anni fa e il comitato di riqualificazione urbana aveva constatato come la sua ricostruzione sarebbe stata uno spreco di risorse preziose. Avevamo raccolto e riciclato le macerie, alcune delle vecchie sale erano state trasformate in circoli letterali e teatrali, altre invece avevano mantenuto la loro vecchia funzione e, quando possibile, si organizzavano serate di cinema all’aperto. Io e Roberta, anni fa, avevamo trovato un modo per accedere all’unica sala rimasta chiusa, diventata subito la nostra preferita: le poltrone erano state portate via, non era rimasto altro che il pavimento, le pareti e il cielo. Era il nostro piccolo segreto, e dopo aver eliminato lo strato di cemento e aver fatto ricrescere la vegetazione naturale, era diventato il luogo in cui, ogni sera, ci incontravamo. Stese sul piccolo prato immerso nel cemento, godevamo del silenzio avvolgente di quel luogo, specialmente dopo la movimentata assemblea di quella sera. Ogni volta che andavamo lì ci divertivamo a cercare nuove costellazioni, attività resa quasi impossibile dal cielo pieno di troppe stelle. Avevamo un piccolo quaderno, riposto in uno scaffale lì a fianco, dove prendevamo nota delle presunte nuove costellazioni cui davamo i nomi più improbabili: “Gerardo”, perché secondo Roberta somigliava al suo gatto, oppure “Il coso che usiamo in laboratorio per la ricrescita cellulare”, sempre un’idea di Roberta che a volte dimenticava i nomi della sua quotidianità. Quella sera però non giocammo, eravamo sfinite dalla giornata di lavoro e dall’assemblea.

“Allora, a te com’è andata oggi?”

“Tutto bene dai, siamo sempre più vicine alla conclusione del progetto di ricerca. Manca poco, lo sento: una volta fatto potremo arginare anche il pericolo del tumore alla pelle, sarebbe veramente una roba assurda”

“Assurdo sì, siete incredibili… ancora non capisco come facciate a pensare queste cose!”

“Beh, io non capisco come voi abbiate fatto a ripristinare i condensatori, meno male che ci hanno indirizzate bene!”

“Sì, a scuola ci hanno visto lungo… e poi, su che altro state lavorando?”

“Guarda, grazie ai risultati di laboratorio della cooperativa medica dell’assemblea Nord Ovest forse riusciremo ad elaborare la formula giusta per poter creare una crema solare in grado di schermare quasi tutte le radiazioni solari. Anche quello sarebbe un gran passo avanti, ma per realizzarlo dobbiamo aspettare le risposte delle compagne ad Afrin, temo ci vorrà ancora un po’.”

Mentre Roberta continuava a parlare, allungai la mano verso la sua arrivando a sfiorarle il palmo. Lei sussultò come al solito, ma per un motivo diverso: era la prima volta che, dopo questo tentativo, il contatto non aveva provocato un aumento delle nostre temperature. Roberta smise di parlare, mosse la mano verso la mia e poggiò tutto il suo palmo sul mio. Trattenendo il respiro, chiusi le dita e le strinsi la mano. Era sopportabile, infinitamente piacevole. Roberta riprese a parlare come se fosse nulla, ma nella sua voce rotta si sentiva l’unicità del momento, tanto che quando girai la testa per guardarle il volto mi accorsi che una lacrima stava scendendo lungo la sua guancia, verso l’orecchio. Mi avvicinai e la asciugai con un bacio, e Roberta smise definitivamente di parlare. Si girò anche lei, con gli occhi pieni di lacrime si avvicinò piano e posò le sue labbra sulle mie. Si ritrasse e scoppiò in un pianto sorridente. Le presi il viso tra le mani e appoggiai la mia fronte sulla sua.

“Aò, ho capito che è la prima volta che riuscimo a baciasse, però certo che sei na piagnona eh! Mica lo so se mo te voglio bacià ancora”

“Giulia ma proprio te parli? Guarda che me l’ha detto prima tu madre, che oggi hai pianto du volte. Che poi scusa, piagni pe i condensatori e non per me? Sono incredibilmente furiosa!”

Ridemmo entrambe, poi tirai fuori un fazzoletto di stoffa e le asciugai il volto. Ci baciammo un’altra volta, poi tornammo a guardare il cielo.

“Robebé guarda! Ce sta na costellazione nuova!”

“Ma che stai dicendo, dai è impossibile! Dove?”

“Segui il mio dito, proprio lì sulla destra. Non l’ho mai vista prima, parono due persone che s’abbracciano.”

“Ah davero, ora la vedo. Ma che carina! Come la chiamiamo?”

Dopo qualche momento di silenzio, all’improvviso Roberta si girò dandomi le spalle dicendomi “potremmo chiamarla “RG”, ma solo se riesci ad abbracciarmi in quel modo”. Piombai nella confusione più totale, ma dopo un po’ riuscii a capire come e dove mettere le braccia: uno sotto il suo collo, l’altro attorno a lei, tra la vita e il suo braccio sinistro. Incredibilmente difficile, incredibilmente piacevole.

“Dormiamo qui?”

“Robbé come famo, domani tocca annà in cooperativa e non c’ho la bici dietro, manco te ce l’hai!”

“Dai Giulia, non ti far pregare. Un modo lo troviamo, non ce la faccio a lasciarti andare adesso”

“Va bene, hai ragione. Non pensiamoci mo, un modo lo troveremo”

Dopotutto, un modo lo avevamo sempre trovato, e avremmo sempre continuato a trovarlo: mai da sole, sempre insieme,

E, ora, abbracciandoci.