Mumtaz Ahmad Numani

(Post-doctoral fellow, Moturi Satyanarayana Centre, Krea University)

Email: mumtaznumani@gmail.com

“Although, this atlas entry titled, “Srinagar in 2200: A Paradise or Paradise Lost?” explores the possible futures for Srinagar city in 2200 while exploring its past and the present ecological histories, I would like to introduce first to the readers Kashmir’s history, with a particular focus on Srinagar’s landscape gardening development culture. This, I hope, will engage readers to understand Srinagar—previously known as the city of gardens. Moreover, after reading this essay, the readers should develop a better understanding of the current landscape dynamics, and will learn about Srinagar’s inspirational ecological past in such a way that they can provide imaginative answers to the two following questions: if ideas and practices from the past were adapted, how would Srinagar look like in 2200? And, if unplanned urbanization continues apace, how differently might Srinagar look in 2200?”

1. Introducing landscape gardening culture:

Although there are several historical accounts that one might rely on to explore Srinagar’s ecological past, however, this essay mostly draws its analysis from Tarikh-i-Hassan[1] which engages its readers to think of the Kashmir’s ecological past, particularly the Srinagar’s landscape gardening culture and its various histories. With that literary substance in account, it [Tarikh-i-Hassan] provides us a lesson on, how historical knowledge can help us understand the ecological past of a city; and also help us imagine more precisely the kinds of futures that the city might have—given the present landscape view and/or unplanned urbanization.

Tarikh-i-Hassan reports that the Rajas (Kings) of Kashmir had developed gardens from the early period (Hassan Khuihami, 1954; Shamsuddin Ahmad, 2003). Therefore, the concept of garden culture in Kashmir goes back to early times before the advent of Islam in the 14th century. A variety of gardens mostly in the form of orchards created in the valley were actually influenced by the concepts of Vatikas (or wooded pleasure gardens) of early India (Mughal Gardens in Kashmir, 2010). These orchards, endowed with a variety of plants (flowers, herbs and fruit plants), were to act as refreshing visiting places for people as are the today’s gardens. For example, among the earliest of such gardens (orchards) in early Kashmir, was the Bagh-i-Toot (Mulberry Garden), first laid out by a Hindu saint Maya Swami and later developed by succeeding Muslim rulers. Maya Swami was a hardworking saintly person living in solitude on the mountain side of Takht-i Sulaiman, who laid-out a wonderful garden on the edges of canal ‘Chounti Kol’, named Takya Maya Swami. The people of the city were visiting this place for refreshment purposes. It is said that, Hazrat Mir Muhammad Hamdani purchased the aforementioned landscape area later on. The landscape area passing through the edges of river Jhelum was first maintained and then connected from Amira Bridge to Takht-i Sulaiman. Afterwards, Hazrat Mir Muhammad Hamdani grafted mulberry trees in large numbers in it, which was endowed as a pasture land for the city animals. Some trees continued to exist until the period of Durrani emperors[2] (Hassan Khuihami, 1954; Shamsuddin Ahmad, 2003). However, the gardens developed and maintained by the Hindu Rajas of Kashmir in early times extinguished over the passage of time. Given the current morphological structure of the Srinagar’s landscape, today, one cannot even locate the original places where these gardens were built in Kashmir. But one might want to know then, how the idea of landscape gardening culture flourished in Kashmir’s Srinagar with an artistic perfection?

It is an established fact that the art of landscape gardening was very much familiar to the Persian people from early times. Here, it bears to mention that, with the establishment of Muslim rule in Kashmir, some knowledgeable leaders from Persia kept coming to Kashmir to be in the court of the rulers. With the passage of time, these innovative immigrants created a great impression among the common people of Kashmir, as well as on the court of the rulers. Among other dozens of things that gradually flourished in Kashmir with the coming of Persian people, the art of landscape gardening stood out as the best.

With these creative Persian immigrants on their courts, the sultans of Kashmir had become very fond of laying beautiful gardens. For example, Sultan Zain-ul-Abideen, lovingly called Bod-Shah[3] (The Great King) among the locals, was a pioneer in creating the most notable gardens in the Valley. He is credited with developing a large beautiful garden on a four-mile square piece of land at Zainagir.[4] To the one side of it, he built towering buildings and on the other side, he planted rows of trees and flower beds; and between these buildings and plants, fountains, water canals and water-falls had been successfully set up. The environs of the garden had become so great that the king and his close aides were frequently making visits to charm themselves. Sultan Zain-ul-Abideen had also built some more beautiful gardens, one of which was built at Na’la-bal[5] (Image 1.1), of Naushera (Images 1.2 and 1.3). To the water arrangements of this garden, a royal canal was dug out from Sind-lar which flowed through the middle of this garden. Hassan informs that the garden was in stable position up to the Sikh rule.[6] (Hassan Khuihami, 1954; Shamsuddin Ahmad, 2003).

The other notable gardens during this period were built by Hussain Shah Chak and Yousuf Shah Chak. Hussain Shah Chak developed a large garden in village Nauhata, which was adjacent to the Shrine of Hazrat Khawaja Moinuddin Naqshbandi (Image 1.4). A water canal by the name of “Lachma-Kol”[7] was brought into the garden; and also, some waterfalls and fountains were built into it. Similarly, Yousuf Shah Chak on the edges of river Jhelum developed a vast garden of different flowers and plants from Fateh Kadal (bridge) to the ghat of Dal hasan yar. This garden consisted of thirteen compartments/stages; and its traces were found till the rule of Afghans in Kashmir (Hassan Khuihami, 1954; Shamsuddin Ahmad, 2003).

Image (1.1): View of the Na’la-bal (watercourse) of Naushera, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (1.2): View of Naushera Srinagar from the side of road. Photograph by the author.

Image (1.3): View of Naushera graveyard. According to the local residents, this is the place where Sultan Zain-ul-abideen had built the large garden. Photograph by the author.

Image (1.4): View of Nauhata chock (adjacent to Jamia Masjid) near Shrine of Hazrat Khawaja Moinuddin Naqshbandi, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Thus, the foregoing description (of the gardens built in pre-Mughal period), derived from the historical accounts, makes it clear that the art of landscape gardening with artistic perfection started with the coming of the Persian immigrants to Kashmir. Those gardens were almost similar in pattern to the Persian gardens. But, what perhaps the Mughals did later, as a report on the Mughal gardens of Kashmir remarkably observes, “was to work on a refinement of the set pattern and thus taking the art of landscape gardening to a new height” (Mughal Gardens in Kashmir, 2010). Thus, one might ask then:Did the Mughals take the art of landscape gardening in Kashmir to a new height for self-gratification only? And, what important lessons those past regional landscape gardening projects communicate to the human cultures across time and space?

Although, nature in any form has always been attractive and gardens of any type contribute, “not only to the look of our landscape, but also to the wisdom of our thinking about the [landscape ecology] and environment” (Mark Francis & Andreas Reimann, 1999). Thus, gardens, particularly in our age, act as a safeguard to the environmental crisis emerging locally and globally. Therefore, scholars wrestling with the core environmental issues consider past and present-day landscape gardening projects as a significant subject of study.

From an environmental perspective, the ruler’s (and/or emperor’s) ecological landscape engagements have been given less attention as far as intellectual wisdom is concerned. Current environmental issues have given us a reason for exploring the ecological landscape engagements in the past for our general understanding. Here, it is noteworthy that the Kashmir’s ecological landscape engagements as a cultural practice have been perceived mostly as an act of leisure and pleasure. This perception emerging from previous scholarly interpretations of the landscape gardens completely negates the richness of human intellectual wisdom shown in the past. This perception also underplays the human character involved in past sustainable development practices. The rulers in the past did not look upon the province of Kashmir just as a pleasure ground; rather their persistent ecological engagement with its landscapes provide a somewhat deeper concern with what now constitute core environmental issues.

2. Srinagar-the city of gardens, lakes and rivers:

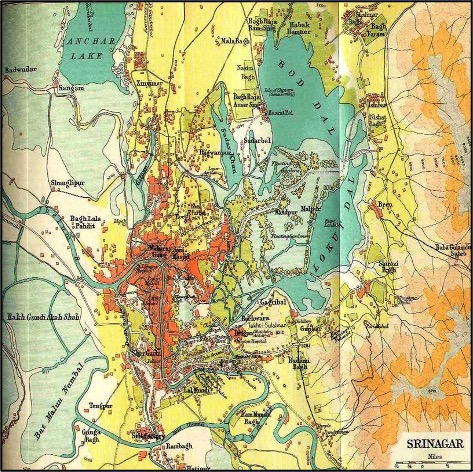

Nowadays, “one can hardly think of a natural system that has not been considerably altered, for better or worse, by human culture” (Foltz et al; 2003). And, if one has to look at the regional level, those landscape changes had occurred in the valley of Kashmir, mostly in the urban city of Srinagar. Srinagar (See Map below), the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, an ancient city with a rich history and culture, situated in the centre of the Kashmir Valley on the banks of the Jhelum River, cannot be imagined without the lakes (For example, Dal lake. Image 2.1), rivers (Jhelum. Image 2.2), and particularly the marvellous landscape gardens (Shalimar and Nishat gardens. Images 2.3 and 2.4). These natural assets and the hundreds of other gardens were planned and commissioned by various rulers, but mostly by the Mughal emperors[8] and their governors in Kashmir. For example, according to Hassan Khuihami[9], not less than six hundred (600) gardens were developed in the Kashmir valley particularly during the Mughal period.Hassan records a short biography of not less than a hundred gardens.However, it is very unfortunate to notice that only a few landscape gardens have survived in the city of Srinagar, which begs the following questions: How did this huge transformation in the landscape of the Srinagar city happen? And/or, how were these landscape gardens extinguished?

As mentioned earlier, in the total number of gardens in Kashmir valley, the maximum number of gardens were developed in Srinagar, mostly around the Dal Lake. Therefore, much like Lahore of Punjab, Srinagar of Kashmir, too deserved an appellation of being called ‘the city of gardens.’ Hassan Khuihami, gives a strange reason for the extinction of most of the landscape gardens in Kashmir. He records: “The animosity between two opposite communities/ groups (or, individuals) often ended up in destroying the valuable properties of each other. In Kashmir, the gardens having an abundance of fruit trees, flower plants and a few beautiful inner buildings were considered the valuable properties. Unfortunately, while taking the revenge against each other, these gardens often became the main target of destruction. For example, a large beautiful garden with several arrangements built at Zainagir by Sultan Zain-ul-Abideen was set on fire during the night by the Pandow Chaks of Trehgam. With this incident, the garden of Zainagir was completely destroyed and never became a garden again” (Hassan Khuihami, 1954). A couple of more incidents of the same nature have been recorded by Hassan.

What Hassan records above might be one of the major reasons for the extinction of the landscape gardens in Kashmir. However, I would like to suggest another reason for the extinction of the landscape gardens in the Srinagar city, particularly around the Dal lake. Srinagar from the very beginning constituted an epicentre of business/trade for the local communities of Kashmir valley. The landless communities who had been temporarily living in the adjacent areas might have been the first of the communities[10] who had settled down on the peripheries of the Dal lake. Moreover, with the decline of the Sultanate, Mughal and other dynastic rulers in Kashmir, the local but comparatively rich communities—who had money and access to businesses opportunities in the city—had also started settling in Srinagar. Therefore, over time, Srinagar had started becoming more populated and urban, which had gradually become the reason for landscape encroachments, and landscape transformation into commercial and permanent residential colonies. For instance, the very nomenclature of Naseem Bagh (Images 2.5 and 2.6),[11] Nageen Bagh (Image 2.7), Aisha Bagh (Image 2.8), Kothi Bagh (Image 2.9), Ram Bagh (Image 2.10), Illahi Bagh (Image 2.11) and Badami Bagh,[12] here I only mention a few, clearly suggests that these were past landscape gardens which had been transformed into the well-established commercial and residential colonies, with large roads and markets inside in the capital city of Srinagar. Such a radical transformation over the years would be cited as an example of ‘development’. But, simultaneously such a ‘development’ has also become a process of ‘erasure’ in which the past landscape gardens have been completely extinguished. Thus, other sets of questions call our attention: What impact does such landscape transformation have on the city ecology and climate? And, what appellation the Srinagar city will deserve in 2200, a paradise or paradise lost?

Over the years, conversion of the garden landscapes along with the agricultural and wetlands around the Dal lake into residential and commercial settlements might have benefited the select communities of Kashmir; but, on a large scale, it appears that this transformation has produced a negative impact on the internal morphology, ecology, and climate of the Srinagar city. Although, the chroniclers, from ancient to early modern times, presented the valley of Kashmir as “Paradise on Earth” and/or “Switzerland of Asia”, particularly around the Dal lake which was often happily referred to by the European chroniclers as “Venice of the East”, however, it is important to note that the present morphological structure and ecological functioning of the waterscapes and landscapes of the city speak volumes against the depicted reality.

Besides, the landscapes around Dal lake (and within the reaches of Dal lake even) have been consistently coming under new unplanned residential and commercial settlements. These new settlements are the direct cause for the decreased size and volume of the city’s green and water landscapes. For example, out of the hundreds of the flourishing green spaces, only a few garden landscapes exist today across the whole of the city. Formerly and around 1200 AD, the world-famous Dal lake-(which is the lifeline of the city), “covered an area of 7500 ha. But now, the lake area was almost reduced to one-third of its size in the 1980s, and was further reduced into one-sixth of its original size in the recent past. In fact, it has lost almost 12 meters’ depth” (R. Mahapatra, 2017).

The rapid illegal encroachments on the city have given birth to unplanned urbanization, which spurred the publication of a dozen articles raising the public concern on the looming ecological crisis across the city in the foreseeable future. These scientific reports suggest that the sustainable existence of the Srinagar city (which as mentioned earlier is mostly dependent on the world-famous Dal lake) is at high risk[13]. This is clear from the fact that the continued illegal encroachments and unplanned urbanization have altered the city’s climate patterns. One such report, prepared by the Centre for Science and Environment observes: “The loss of water bodies, and green landscapes (italics added) of Srinagar has, in fact, a bearing on the microclimate of the city, as meteorological data recorded during the past century suggests a rising trend in the mean maximum temperatures during the summers[14]. On July 15, 1973, the highest temperature ever recorded in Srinagar was 35.5 ºC. On July 7, 2006, it rose to 39.5 ºC. It is suggested that the rise in mean annual temperature in the area is mainly due to loss of water bodies, and green landscapes, since a considerable amount of evapotranspiration with a cooling effect might have been taking place in the past due to these valuable ecological assets during summers. What is more, the construction boom often leads to an increase in summer temperatures due to the creation of urban heat islands” (Soma Basu, 2014).

The report quoted above suggests that the loss of green landscapes and waterscapes occurred over the years have a direct bearing on the ecological functioning of the Srinagar city, which signals that the practice of illegal city encroachments and unplanned urbanization has not stopped and, henceforth, the city which was known as the city of gardens, lakes and rivers, and deserved the appellation of “Paradise on Earth”, “Switzerland of Asia” and/or “Venice of the East”might fall in the category of a dystopian city and/or a paradise lostin 2200?

Reflection: This essay structured in two parts is a non-fictional creative story mostly derived from reliable historical knowledges. Does the historical (and/or scientific) data “quoted” in the essay authenticates us to see the Srinagar city happening without the world-famous Dal lake & the landscape gardens in the next hundreds of years? Can our wisdom afford to see that? And, what would that be called in environmental humanities, ‘development’ and/ or ‘erasure of ecological past’?

Map[15]: Indicates the topography of Srinagar, which is the summer capital city of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, India (UT after post-August 2019). The map was prepared in 1924. Source: Adopted from Department of Ecology, Environment and Remote Sensing, Bemina Srinagar-10.

Image (2.1): View of the Dal Lake, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.2): View of the river Jhelum from the side of Raj Bagh, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.3): Views of the Shalimar garden, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.4): Views of the Nishat garden, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.5): View of the Naseem Bagh (inside campus, University of Kashmir). Photograph by the author.

Image (2.6): View of the Naseem Bagh from the side of Dal lake (right side). Photograph by the author.

Image (2.7): Views of the Nageen Lake (bottom), and Nageen Bagh (top), Srinagar. Photographs by the author.

Image (2.8): View of the Aisha Bagh adjacent to Nageen Lake, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.9): View of the Kothi Bagh, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.10): Views of the Ram Bagh, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

Image (2.11): View of the Ellahi Bagh, Srinagar. Photograph by the author.

References:

- Basu, S. (08 September, 2014). Unplanned urbanisation, encroachment blamed for Srinagar flood. Down to Earth Magazine.

- Foltz, Richard C. et al; (Eds.), (2003). Islam and Ecology, Harvard University Press.

- Khuihami, Peer Ghulam Hassan. Tarikh-i-Hassan, (Ed.), Sahibzada Hassan Shah, (Srinagar, 1954) Vol. 1st, The Research and Publication Department, Srinagar, pp. 281-283, 306; Ahmad, Shamsuddin. Urdu transl. Shams-ut-Tawarikh, (Srinagar, 2003), Vol. 1st. pp. 293-294, 313.

- Mahapatra, Richard et al; (Eds.), (2017). Environment Reader, Centre for science and environment, New Delhi, p.28.

- See, Mughal Gardens in Kashmir (2010). Report submitted by Permanent Delegation of India to UNESCO, (Ref. 5580).

- Pollan, M. Beyond Wilderness and Lawn, cited in Francis, M & Reimann, A. (1999). The California Landscape Garden: Ecology, Culture and Design, University of California Press, p. XIII.

[1] Tarikh-i-Hassan of Peer Ghulam Hassan Khuihami originally written in the Persian language (in two volumes) is one of the acclaimed historical accounts that better informs us the historical ecology of the Kashmir, which includes the Srinagar’s ecological past.

[2] The Durrani rulers (Afghans) remained in power in Kashmir from 1752 to 1819 A.D.

[3] In Kashmiri language ‘Bod’ means ‘Great’ and ‘Shah’ during the medieval period was referred to ‘King’.

[4] Zainagir at present is in Sopore of Baramulla district of Jammu and Kashmir.

[5] Na’la means watercourse in the Urdu language.

[6] Here, it bears to mention that Mughals remained in power in Kashmir from 1586 to 1752 A.D. Thereafter started the Afghan rule which remained in power from 1752 to 1819 A.D. And Afghans were then overpowered by the Sikhs who remained in power in Kashmir from 1819 to 1846 A.D.

[7] Water canal in the Kashmiri language is called Kol.

[8] Kashmir was annexed to the Mughal rule by emperor Akbar in 1586 A.D., and Mughals remained in power in Kashmir from 1586 to 1752 A.D.

[9] Peer Ghulam Hassan Khuihami was the reputable historiographer of Kashmir. He has authored Tarikh-i-Hassan in two volumes in the Persian language. Tarikh-i-Hassan is considered one of the principal historical scholars on the political and geographical history of Kashmir.

[10] See, Tarikh-i-Hassan Vol. 2, 13th Awrang/ Chapter on the period of Afghan rule in Kashmir (especially the period of Amir Khan Jawansher), mentions, how Hanjis/ Han’z/ Fisher communities (in Urdu, Kashmiri and English languages) of Nandpur had destroyed the gardens of Dal Lake.

[11] Bagh in Kashmiri (and Urdu) languages means garden. And, Naseem Bagh means, the garden of breeze.

[12] Badami Bagh adjacent to Dal Gate Srinagar is a Cantonment town now.

[13] See, Romshoo, S.A; and I. Rashid. (2012). Assessing the Impacts of Changing Land Cover and Climate on Hokersar Wetland in Indian Himalayas. Arabian Journal of Geoscience. Wani, R. A. (2012). Impact of Areal and Demographic Changes on Urban Growth of Srinagar City. Journal of Chemical, Biological and Physical Sciences.

[14] Green landscapes refer to garden landscapes.

[15] Here it is noteworthy that Dal Lake is divided into two parts. In the Map ‘Bod Dal’ in Kashmiri language means ‘larger part of the Dal lake’ and ‘Lokut Dal’ means ‘smaller part of the Dal lake’.